Marketplace

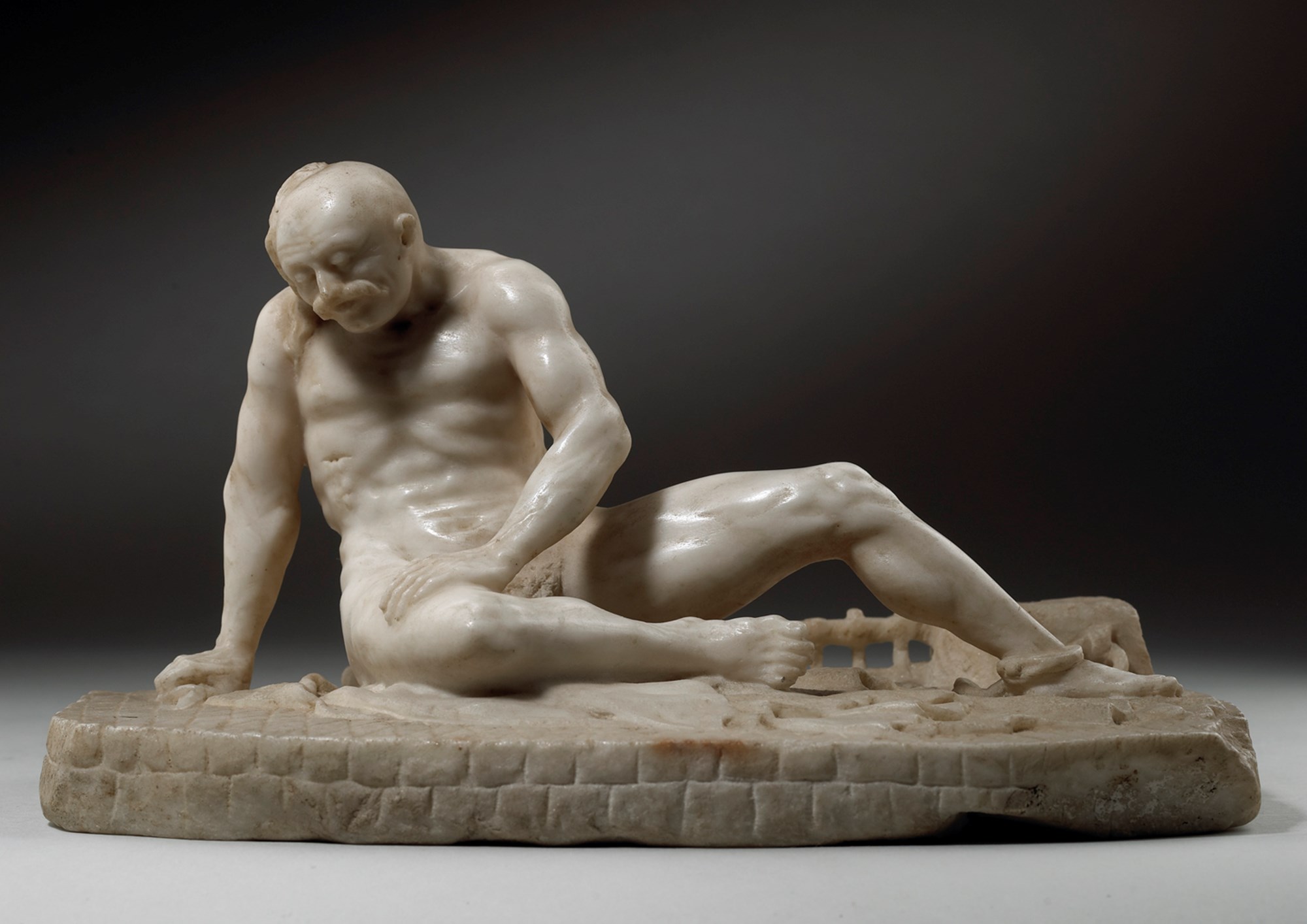

23. A Turk Represented as the Model of The Dying Gaul

Francesco Bertos

23. A Turk Represented as the Model of The Dying Gaul

Medium White marble

Dimension 17 x 29 cm (6³/₄ x 11³/₈ inches)

This finely carved marble is a copy after the antique, of the ancient sculpture known as the Dying Gaul, in the Capitoline Museum in Rome. The ancient marble statue was first recorded in the 1623 inventory of the Ludovisi collection in Rome, where it was described as a dying gladiator. By 1633, the sculpture had been relocated to the Palazzo Grande on the Ludovisi estate on the Pincio. Aside from a brief period during which it was confiscated by Don Livio Odescalchi as compensation for an outstanding debt, the Dying Gaul remained in the possession of the Ludovisi family until shortly before 1737, when it was acquired by Pope Clement XII (1652-1740) for the Capitoline Museum. Following the Treaty of Tolentino in 1797, it came into the possession of the French and was taken to France. However, in the aftermath of Napoleon’s defeat, it was repatriated to Rome in 1816, where it was reinstated in the Capitoline Museum, where it resides today.

A touching testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the Dying Gaul depicts a fallen warrior in his final moments before succumbing to a fatal abdominal wound. Since its discovery, the sculpture was erroneously believed to represent a gladiator at the moment of death, however, the presence of a broken horn prompted the renowned German art historian and antiquarian J. J. Winckelmann to reassess the subject, suggesting instead that the sculpture depicted a Greek herald (H&P 1981 p226). It was the Roman art historian and antiquarian E. Q. Visconti (1751-1818) who instead argued that the figure’s physiognomy and ethnic characteristics identified him as a defeated barbarian warrior, likely a Gaul or a German, who had perished heroically on the battlefield (H&P 1981 p226). By the mid-nineteenth century, scholarly consensus agreed with Visconti’s view, that the sculpture did indeed represent a Gallic warrior, with defining features such as his moustache, thick matted hair, and the torque around his neck; such characteristic attributes mark him as a member of one of the Celtic tribes, whom the Greeks and Romans regarded as barbarians. Since its discovery, the Dying Gaul has been widely celebrated by artists and collectors alike. Its fame spread quickly throughout Europe as the result of an etching published in Rome in 1638 by François Perrier (1590-1650). Plaster casts of the sculpture further contributed to its prestige, with notable commissions for King Philip IV of Spain (1605-1665) and the French Academy in Rome, followed by a lifesize marble replica of the sculpture by Michel Monnier on the order of Louis XIV (1638-1715). Various large-scale copies were also realised in England, such as a stone version by Peter Scheemakers for the garden at Rousham, Oxfordshire, one in marble by Simon Vierpyl for Lord Pembroke’s Wilton House in Wiltshire, and a bronze cast by Luigi Valadier for the grand hall of the Duke of Northumberland’s mansion at Syon. Further bronze casts were realised by Gianfrancesco Susini (1585-1653) in the seventeenth century, followed by Giovanni Zoffoli (c. 1745-1805) in the eighteenth century. Given greatest prominence in Giovanni Paolo Panini’s gallery of ancient art, the Dying Gaul served as a significant source of artistic inspiration, influencing works such as Diego Velázquez’s Mercury and Argus (Museo del Prado, Madrid, inv. P001175) and Jacques-Louis David’s Male Nude Study, called Patroclus (Musée Thomas Henry, Cherbourg). The study and replication of the sculpture, in its various forms and reductions, did not only become de riguer for art students, but also an unmissable stop for Grand Tourists. Whilst on his tour of Italy in the years 1816-1823, Lord Byron eloquently commemorated the statue in his poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

I see before me the Gladiator lie:

He leans upon his hand – his manly brow

Consents to death, but conquers agony,

And his droop’d head sinks gradually low –

And through his side the last drops, ebbing slow

From the red gash, fall heavy, one by one,

Like the first of a thunder-shower; and now

The arena swims around him – he is gone,

Ere ceased the inhuman shout which hail’d

the wretch who won.

Francesco Bertos (active c. 1693–1730s) was an Italian sculptor known for his distinctive and highly decorative style, which blended elements of Mannerism and Rococo. Though little is known about his early life, he was first documented in Rome in 1693 and later as an active sculptor in Venice by 1710. His work, primarily secular in nature, was especially popular among foreign collectors, particularly British visitors to Italy. Unlike many of his contemporaries who drew inspiration from classical antiquity, Bertos developed a neo-Mannerist approach, emphasizing artificiality, refinement, and dynamic composition. Bertos reinterpreted Mannerism as a form of hedonistic artificiality, characterized by highly polished surfaces, softly tensed forms, and, at times, exceptionally refined craftsmanship. The majority of his commissions came from private patrons, which influenced his selection of subjects, typically mythological or allegorical in nature. However, his compositions often contain a degree of ambiguity, perhaps deliberately catering to the intellectual and aesthetic sensibilities of his sophisticated clientele. His work was esteemed highly enough to be included in one of the most significant artistic collections in Venice at the time, that of Zaccaria Sagredo (1653–1729), procurator of St. Mark’s. Bertos’ reputation secured him a commission around 1724 from Marshal Schulenburg for a series of bronzes, including an equestrian portrait. Bertos was particularly adept at small-scale sculpture and medium-sized bronzes. In these collector’s pieces, his style is predominantly decorative, lacking structural logic, and reflecting the Rococo painters’ most innovative decorative tendencies. His sculptural compositions feature intricate, sinuous forms that embody the exuberant dynamism of the Rococo aesthetic.

A bronze group by Bertos in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, presents a vivid depiction of a vanquished Turk, whose severed head can be seen at the end of a spear wielded by a male warrior. The complex iconography of the group has led scholars to the patronage of Field Marshal Count Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (1661-1747). Serving as commander in chief of the forces of the Venetian Republic from 1715, Schulenburg gained renown for his defence of Corfu against the Ottoman forces in 1715-1716, an achievement which elevated him to the status of a Venetian hero. In recognition of his service, the Venetians honoured him with a commemorative statue and granted him a lifelong pension. Following his retirement to Venice in 1724, Schulenburg took residence at Palazzo Loredan, where he assembled a distinguished collection of paintings and sculptures. Between 1732 and 1733, he commissioned multiple works in both bronze and marble from Bertos.1

Although Bertos is known to have created miniature works primarily as an exercise in artistic experimentation, this particular work, perhaps commissioned by Schulenburg himself, can be interpreted as a playful yet sophisticated reimagining of the classical motif of the vanquished soldier, serving as an allegorical representation of the Venetian triumph over the Ottoman Empire.

A touching testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the Dying Gaul depicts a fallen warrior in his final moments before succumbing to a fatal abdominal wound. Since its discovery, the sculpture was erroneously believed to represent a gladiator at the moment of death, however, the presence of a broken horn prompted the renowned German art historian and antiquarian J. J. Winckelmann to reassess the subject, suggesting instead that the sculpture depicted a Greek herald (H&P 1981 p226). It was the Roman art historian and antiquarian E. Q. Visconti (1751-1818) who instead argued that the figure’s physiognomy and ethnic characteristics identified him as a defeated barbarian warrior, likely a Gaul or a German, who had perished heroically on the battlefield (H&P 1981 p226). By the mid-nineteenth century, scholarly consensus agreed with Visconti’s view, that the sculpture did indeed represent a Gallic warrior, with defining features such as his moustache, thick matted hair, and the torque around his neck; such characteristic attributes mark him as a member of one of the Celtic tribes, whom the Greeks and Romans regarded as barbarians. Since its discovery, the Dying Gaul has been widely celebrated by artists and collectors alike. Its fame spread quickly throughout Europe as the result of an etching published in Rome in 1638 by François Perrier (1590-1650). Plaster casts of the sculpture further contributed to its prestige, with notable commissions for King Philip IV of Spain (1605-1665) and the French Academy in Rome, followed by a lifesize marble replica of the sculpture by Michel Monnier on the order of Louis XIV (1638-1715). Various large-scale copies were also realised in England, such as a stone version by Peter Scheemakers for the garden at Rousham, Oxfordshire, one in marble by Simon Vierpyl for Lord Pembroke’s Wilton House in Wiltshire, and a bronze cast by Luigi Valadier for the grand hall of the Duke of Northumberland’s mansion at Syon. Further bronze casts were realised by Gianfrancesco Susini (1585-1653) in the seventeenth century, followed by Giovanni Zoffoli (c. 1745-1805) in the eighteenth century. Given greatest prominence in Giovanni Paolo Panini’s gallery of ancient art, the Dying Gaul served as a significant source of artistic inspiration, influencing works such as Diego Velázquez’s Mercury and Argus (Museo del Prado, Madrid, inv. P001175) and Jacques-Louis David’s Male Nude Study, called Patroclus (Musée Thomas Henry, Cherbourg). The study and replication of the sculpture, in its various forms and reductions, did not only become de riguer for art students, but also an unmissable stop for Grand Tourists. Whilst on his tour of Italy in the years 1816-1823, Lord Byron eloquently commemorated the statue in his poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

I see before me the Gladiator lie:

He leans upon his hand – his manly brow

Consents to death, but conquers agony,

And his droop’d head sinks gradually low –

And through his side the last drops, ebbing slow

From the red gash, fall heavy, one by one,

Like the first of a thunder-shower; and now

The arena swims around him – he is gone,

Ere ceased the inhuman shout which hail’d

the wretch who won.

Francesco Bertos (active c. 1693–1730s) was an Italian sculptor known for his distinctive and highly decorative style, which blended elements of Mannerism and Rococo. Though little is known about his early life, he was first documented in Rome in 1693 and later as an active sculptor in Venice by 1710. His work, primarily secular in nature, was especially popular among foreign collectors, particularly British visitors to Italy. Unlike many of his contemporaries who drew inspiration from classical antiquity, Bertos developed a neo-Mannerist approach, emphasizing artificiality, refinement, and dynamic composition. Bertos reinterpreted Mannerism as a form of hedonistic artificiality, characterized by highly polished surfaces, softly tensed forms, and, at times, exceptionally refined craftsmanship. The majority of his commissions came from private patrons, which influenced his selection of subjects, typically mythological or allegorical in nature. However, his compositions often contain a degree of ambiguity, perhaps deliberately catering to the intellectual and aesthetic sensibilities of his sophisticated clientele. His work was esteemed highly enough to be included in one of the most significant artistic collections in Venice at the time, that of Zaccaria Sagredo (1653–1729), procurator of St. Mark’s. Bertos’ reputation secured him a commission around 1724 from Marshal Schulenburg for a series of bronzes, including an equestrian portrait. Bertos was particularly adept at small-scale sculpture and medium-sized bronzes. In these collector’s pieces, his style is predominantly decorative, lacking structural logic, and reflecting the Rococo painters’ most innovative decorative tendencies. His sculptural compositions feature intricate, sinuous forms that embody the exuberant dynamism of the Rococo aesthetic.

A bronze group by Bertos in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, presents a vivid depiction of a vanquished Turk, whose severed head can be seen at the end of a spear wielded by a male warrior. The complex iconography of the group has led scholars to the patronage of Field Marshal Count Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (1661-1747). Serving as commander in chief of the forces of the Venetian Republic from 1715, Schulenburg gained renown for his defence of Corfu against the Ottoman forces in 1715-1716, an achievement which elevated him to the status of a Venetian hero. In recognition of his service, the Venetians honoured him with a commemorative statue and granted him a lifelong pension. Following his retirement to Venice in 1724, Schulenburg took residence at Palazzo Loredan, where he assembled a distinguished collection of paintings and sculptures. Between 1732 and 1733, he commissioned multiple works in both bronze and marble from Bertos.1

Although Bertos is known to have created miniature works primarily as an exercise in artistic experimentation, this particular work, perhaps commissioned by Schulenburg himself, can be interpreted as a playful yet sophisticated reimagining of the classical motif of the vanquished soldier, serving as an allegorical representation of the Venetian triumph over the Ottoman Empire.

Medium: White marble

Dimension: 17 x 29 cm (6³/₄ x 11³/₈ inches)

Provenance: Probably commissioned for Field Marshall Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (1661-1747)

Private collection, France

More artworks from the Gallery