Marketplace

The Quarrel of the Queens: Kriemhild and Brunhild at the Church, from Das Nibelungenlied [recto]; Kriemhild and Brunhild, with Siegfried Between Them [verso]

Henry FUSELI RA

The Quarrel of the Queens: Kriemhild and Brunhild at the Church, from Das Nibelungenlied [recto]; Kriemhild and Brunhild, with Siegfried Between Them [verso]

In the early years of the 19th century Henry Fuseli began to depict subjects and characters from the medieval German epic poem the Nibelungenlied (or the Song of the Nibelungs) in a number of oil paintings and drawings, and he continued to produce works inspired by the text until 1820. Fuseli was well acquainted with the tale; his teacher Bodmer had been the first to publish a portion of the Nibelungenlied in 1755 and he himself owned the first German edition of the full text, published in 1782. (The poem was not translated into English until 1848 and so would have been largely unknown to a British audience.) Fuseli exhibited paintings of scenes from the Nibelungenlied at the Royal Academy in 1807 and between 1814 and 1820, and also wrote a number of poems based on the text.

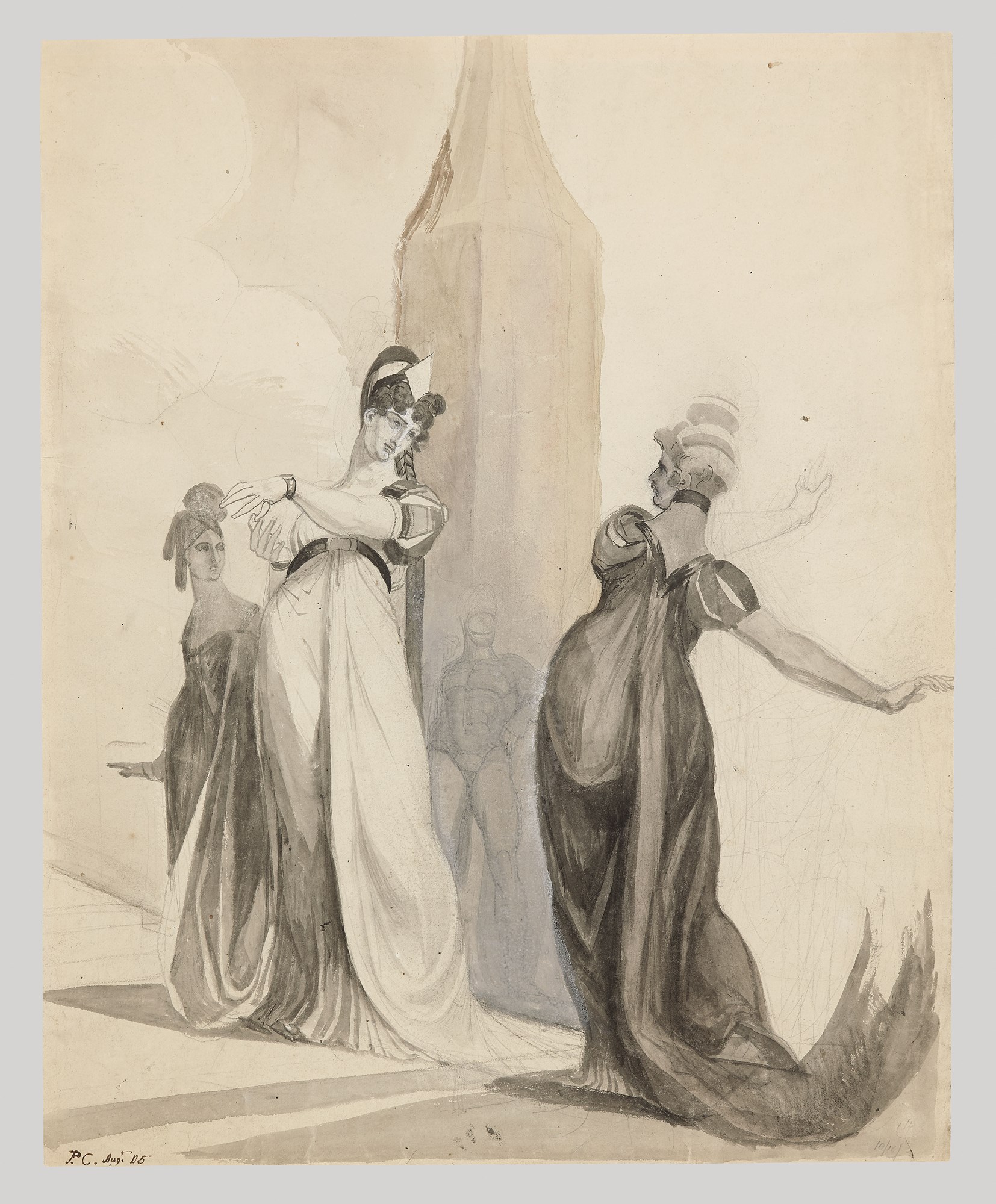

Between 1805 and 1807 Fuseli produced a series of large, finished drawings of episodes from the Nibelungenlied, of which the present sheet is one. A recurring character in most of these works is that of Kriemhild, the central female protagonist of the story. As a recent scholar has suggested, ‘Kriemhild is Henry Fuseli’s representation of the ideal woman, embodying values of justice and morality.’ A Burgundian princess, Kriemhild married the great warrior prince Siegfried, but their love is shattered when Siegfried is murdered by Hagen, a close friend of Kriemhild’s brother, the Burgundian King Gunther, during a boar hunt. Kriemhild’s grief is overwhelming, and the remainder of the story is taken up with her search for revenge, culminating in the savage deaths of Gunther and Hagen, and the destruction of the Burgundian kingdom. As Christian Klemm points out, ‘[one] aspect that particularly fascinated Fuseli in the Nibelungenlied [was] Kriemhild’s manically obsessive revenge, which is no less excessive and without restraint than her possessive love.’

This large sheet is part of a distinct series of Nibelungenlied drawings, executed between May and August 1805, and represents an episode from the first half of the poem, before the death of Siegfried. Here Kriemhild challenges her rival, the warrior-queen Brunhild, wife of King Gunther. The two women have argued over which has the higher social rank, since Brunhild wrongly believes that Siegfried is Gunther’s vassal, and that therefore she, as the wife of a King, should take precedence. Meanwhile, Kriemhild claims that Siegfried, not Gunther, took Brunhild’s virginity on her wedding night, when he took her ring and belt as trophies. (Although Siegfried did not, in fact, seduce Brunhild that night, he did steal her ring and belt, with the help of a magical cloak of invisibility.)When both women arrive at the cathedral at the same time, Kriemhild asserts her superior status and enters first, to Brunhild’s anger and dismay.

As Klemm describes the present sheet, Fuseli ‘presents the fight between the two Queens in an elaborately orchestrated climax in front of the church, where Brunhild tries to deny precedence to Kriemhild and Kriemhild accuses Brunhild of being her husband’s concubine, leading to the tragedy after the mass, when Kriemhild shows the ring and belt Siegfried took from Brunhild on her wedding night...Fuseli was in every way equal to the dramatic mastery with which his literary model employs contrasts to reveal the antagonism of the two rivals; in fact he builds up the situation even further, following his predilection for diametric opposites, by contracting the whole sequence of the narrative into one single scene. Kriemhild, as the wife of the great hero Siegfried, is portrayed all in white apart from the belt which Brunhild, in black, is missing; this woman bright with light who drags the secret concealed in the darkness into the daylight is show frontally, while her opponent in diametrically opposed rear view turns back. Kriemhild strides past her up the steps of the cathedral, showing the ring with a contemptuous gesture. As in the saga, standing between the fighting queens is the object of their dispute, the enigmatic Siegfried: shadow-like, he seems to be more part of than in front of a steeply soaring geometric form, which may be seen in concrete terms as a buttress of the church. But the significance of the scene lies wholly in the abstract expressive content – in the division of the picture plane between the rivals, opening up a height and depth giving the conflict both suspense and inevitability.’ It is this quarrel between Kriemhild and Brunhild, and the anger which the latter feels at being deceived and dishonoured, that leads her to demand justice from Gunther, who then orders Hagen to kill Siegfried.

Other drawings of subjects from the Nibelungenlied from 1805 are today in the collections of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki in New Zealand, the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the Nottingham City Museums and Galleries, the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar and the Kunsthaus in Zurich. As the Fuseli scholar Gert Schiff has noted, ‘In just a few months, mostly at Joseph Johnson’s country estate, he created a series of Nibelungen drawings that are among his finest achievements; had this series not remained fragmentary, this series could have been his masterpiece.’

The verso of this double-sided sheet shows the figure of Kriemhild traced through from the recto, creating a reversed image, to which the artist has added the figures of Brunhilde and Siegfried in different poses from the recto. This allowed him to experiment with variations to the composition, and is typical of Fuseli’s practice, since he often drew through the outlines of figures onto the versos of his drawings, which he then elaborated upon. As Ketty Gottardo has written, ‘Fuseli’s frequent practice of tracing his compositions from one side to the other of a sheet in order to obtain a mirror image…happens so frequently in his work that it could almost be considered a trademark of authenticity of the artist’s drawings, in addition to their left-handedness…for Fuseli the point of tracing through from one side of a sheet to the other was not simply about seeing how a composition would appear when turned in the opposite direction. On the contrary, trying out a design on the other side allowed him to experiment, and to play with certain details; at times he would then return to the side drawn first to make changes there…through tracing, Fuseli’s explorations on paper free his fantasy to exploit different ideas.’

In his Nibelungenlied drawings, as has been noted, ‘Fuseli’s visual representation of Kriemhild is an idealized figure of Justice. She is depicted with an androgynous form consisting of both masculine and feminine features, including a strong physique and a furrowed brow, exuding absolute strength and force, alongside a shapely body and long flowing hair. This androgyny…mixes together strength and femininity…Several of the drawings from the 1805 series present Kriemhild as the largest and most detailed figure in the scene, making her a central and hierarchically important figure. Not only does this emphasize Fuseli’s interest in the character, it also shows the depth of Kriemhild and her journey towards rectifying a wrongful act.’ Although in Fuseli’s Nibelungenlied drawings the men are usually depicted as antique nudes, the women, and in particular Kriemhild, are shown in contemporary fashions and hairstyles, typified by the Neoclassical Empire dresses of the early years of the 19th century. As has also been noted, ‘Fuseli was especially interested in changes in women’s fashions.’

The initials P.C. inscribed by Fuseli at the bottom of the present sheet indicate that it was one of the drawings made by the artist at the country home, at Purser’s Cross in Fulham, of his longtime friend, the publisher and bookseller Joseph Johnson (1738-1809). Johnson is perhaps best-known today as the publisher of William Blake’s engravings, but also published the works of such writers as William Beckford, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Cowper, Erasmus Darwin, William Godwin, Thomas Malthus, Joseph Priestley, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Wordsworth. When Fuseli first arrived in London from Zurich in 1764 Johnson allowed him to stay in a flat above his bookshop in St. Paul’s Churchyard, and engaged him as a translator while Fuseli began to pursue his artistic ambitions. As one scholar has written, ‘Secure in his profession and recognized as one of its leaders, Johnson obtained for himself the sine qua non of an established tradesman: a house in the suburbs. He rented Acacia Cottage in Fulham where he spent weekends entertaining his intimate friends. Fuseli and Joseph Farington of the Royal Academy came often for dinner and a game of whist. Fuseli usually brought his sketch book, identifying his completed drawings with his signature and the initials “P.C.” for “Purser’s Cross”, the location of his host’s cottage.’ Most of Fuseli’s Nibelungenlieddrawings of 1805 were done at Purser’s Cross, and several examples – dated between May and November 1805 – are in the museums of Auckland, Berlin, Weimar and Zurich.

Between 1805 and 1807 Fuseli produced a series of large, finished drawings of episodes from the Nibelungenlied, of which the present sheet is one. A recurring character in most of these works is that of Kriemhild, the central female protagonist of the story. As a recent scholar has suggested, ‘Kriemhild is Henry Fuseli’s representation of the ideal woman, embodying values of justice and morality.’ A Burgundian princess, Kriemhild married the great warrior prince Siegfried, but their love is shattered when Siegfried is murdered by Hagen, a close friend of Kriemhild’s brother, the Burgundian King Gunther, during a boar hunt. Kriemhild’s grief is overwhelming, and the remainder of the story is taken up with her search for revenge, culminating in the savage deaths of Gunther and Hagen, and the destruction of the Burgundian kingdom. As Christian Klemm points out, ‘[one] aspect that particularly fascinated Fuseli in the Nibelungenlied [was] Kriemhild’s manically obsessive revenge, which is no less excessive and without restraint than her possessive love.’

This large sheet is part of a distinct series of Nibelungenlied drawings, executed between May and August 1805, and represents an episode from the first half of the poem, before the death of Siegfried. Here Kriemhild challenges her rival, the warrior-queen Brunhild, wife of King Gunther. The two women have argued over which has the higher social rank, since Brunhild wrongly believes that Siegfried is Gunther’s vassal, and that therefore she, as the wife of a King, should take precedence. Meanwhile, Kriemhild claims that Siegfried, not Gunther, took Brunhild’s virginity on her wedding night, when he took her ring and belt as trophies. (Although Siegfried did not, in fact, seduce Brunhild that night, he did steal her ring and belt, with the help of a magical cloak of invisibility.)When both women arrive at the cathedral at the same time, Kriemhild asserts her superior status and enters first, to Brunhild’s anger and dismay.

As Klemm describes the present sheet, Fuseli ‘presents the fight between the two Queens in an elaborately orchestrated climax in front of the church, where Brunhild tries to deny precedence to Kriemhild and Kriemhild accuses Brunhild of being her husband’s concubine, leading to the tragedy after the mass, when Kriemhild shows the ring and belt Siegfried took from Brunhild on her wedding night...Fuseli was in every way equal to the dramatic mastery with which his literary model employs contrasts to reveal the antagonism of the two rivals; in fact he builds up the situation even further, following his predilection for diametric opposites, by contracting the whole sequence of the narrative into one single scene. Kriemhild, as the wife of the great hero Siegfried, is portrayed all in white apart from the belt which Brunhild, in black, is missing; this woman bright with light who drags the secret concealed in the darkness into the daylight is show frontally, while her opponent in diametrically opposed rear view turns back. Kriemhild strides past her up the steps of the cathedral, showing the ring with a contemptuous gesture. As in the saga, standing between the fighting queens is the object of their dispute, the enigmatic Siegfried: shadow-like, he seems to be more part of than in front of a steeply soaring geometric form, which may be seen in concrete terms as a buttress of the church. But the significance of the scene lies wholly in the abstract expressive content – in the division of the picture plane between the rivals, opening up a height and depth giving the conflict both suspense and inevitability.’ It is this quarrel between Kriemhild and Brunhild, and the anger which the latter feels at being deceived and dishonoured, that leads her to demand justice from Gunther, who then orders Hagen to kill Siegfried.

Other drawings of subjects from the Nibelungenlied from 1805 are today in the collections of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki in New Zealand, the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the Nottingham City Museums and Galleries, the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar and the Kunsthaus in Zurich. As the Fuseli scholar Gert Schiff has noted, ‘In just a few months, mostly at Joseph Johnson’s country estate, he created a series of Nibelungen drawings that are among his finest achievements; had this series not remained fragmentary, this series could have been his masterpiece.’

The verso of this double-sided sheet shows the figure of Kriemhild traced through from the recto, creating a reversed image, to which the artist has added the figures of Brunhilde and Siegfried in different poses from the recto. This allowed him to experiment with variations to the composition, and is typical of Fuseli’s practice, since he often drew through the outlines of figures onto the versos of his drawings, which he then elaborated upon. As Ketty Gottardo has written, ‘Fuseli’s frequent practice of tracing his compositions from one side to the other of a sheet in order to obtain a mirror image…happens so frequently in his work that it could almost be considered a trademark of authenticity of the artist’s drawings, in addition to their left-handedness…for Fuseli the point of tracing through from one side of a sheet to the other was not simply about seeing how a composition would appear when turned in the opposite direction. On the contrary, trying out a design on the other side allowed him to experiment, and to play with certain details; at times he would then return to the side drawn first to make changes there…through tracing, Fuseli’s explorations on paper free his fantasy to exploit different ideas.’

In his Nibelungenlied drawings, as has been noted, ‘Fuseli’s visual representation of Kriemhild is an idealized figure of Justice. She is depicted with an androgynous form consisting of both masculine and feminine features, including a strong physique and a furrowed brow, exuding absolute strength and force, alongside a shapely body and long flowing hair. This androgyny…mixes together strength and femininity…Several of the drawings from the 1805 series present Kriemhild as the largest and most detailed figure in the scene, making her a central and hierarchically important figure. Not only does this emphasize Fuseli’s interest in the character, it also shows the depth of Kriemhild and her journey towards rectifying a wrongful act.’ Although in Fuseli’s Nibelungenlied drawings the men are usually depicted as antique nudes, the women, and in particular Kriemhild, are shown in contemporary fashions and hairstyles, typified by the Neoclassical Empire dresses of the early years of the 19th century. As has also been noted, ‘Fuseli was especially interested in changes in women’s fashions.’

The initials P.C. inscribed by Fuseli at the bottom of the present sheet indicate that it was one of the drawings made by the artist at the country home, at Purser’s Cross in Fulham, of his longtime friend, the publisher and bookseller Joseph Johnson (1738-1809). Johnson is perhaps best-known today as the publisher of William Blake’s engravings, but also published the works of such writers as William Beckford, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Cowper, Erasmus Darwin, William Godwin, Thomas Malthus, Joseph Priestley, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Wordsworth. When Fuseli first arrived in London from Zurich in 1764 Johnson allowed him to stay in a flat above his bookshop in St. Paul’s Churchyard, and engaged him as a translator while Fuseli began to pursue his artistic ambitions. As one scholar has written, ‘Secure in his profession and recognized as one of its leaders, Johnson obtained for himself the sine qua non of an established tradesman: a house in the suburbs. He rented Acacia Cottage in Fulham where he spent weekends entertaining his intimate friends. Fuseli and Joseph Farington of the Royal Academy came often for dinner and a game of whist. Fuseli usually brought his sketch book, identifying his completed drawings with his signature and the initials “P.C.” for “Purser’s Cross”, the location of his host’s cottage.’ Most of Fuseli’s Nibelungenlieddrawings of 1805 were done at Purser’s Cross, and several examples – dated between May and November 1805 – are in the museums of Auckland, Berlin, Weimar and Zurich.

Provenance: Private collection, Switzerland, in 1973

Private collection, Germany.

Literature: Gert Schiff, Johann Heinrich Füssli 1741-1825, Zürich, 1973, Vol.I, p.317, pp.638-639, no.1798, Vol.II, fig.1798 [recto]; Christian Klemm, ‘Friedel’s Love and Kriemhild’s Revenge. Fuseli’s Revels in the Kingdom of the Nibelungs’, in Franziska Lentzsch et al, Fuseli: The Wild Swiss, exhibition catalogue, Zurich, 2005-2006, pp.160-162 (recto only illustrated).

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie

-DELLE SITE-Sogno dell’ aviere (The Dream of the Airman)_T638114469830049470.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)