Marketplace

13. Equestrian Statue of Emperor Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (1608 – 1657)

13. Equestrian Statue of Emperor Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (1608 – 1657)

Medium Bronze

The reappearance of this outstanding bronze of Emperor Ferdinand III on horseback after more than thirty years provides an opportunity for a fresh look at the equestrian bronze statuettes attributed to Caspar Gras. This cast and a companion bronze of Philip IV of Spain first came to light with the Galleria Sangiorgi at the beginning of the 20th century. Their elaborate ebonised wooden bases confirm that they have long, if not always, formed pendants. They are significant additions to the series of bronze equestrian statuettes that Gras made of European rulers, the vast majority from the ruling Habsburg dynasty.

As in recent years Antonio Susini and Pietro Tacca have emerged from the towering shadow of Giambologna south of the Alps, so too Caspar Gras has increasingly been understood as a distinct and notable artistic personality in relation to Hubert Gerhard north of the Alps. However, whilst recent biographical summaries have focused on Gerhard’s influence on Gras, the most complete biography of the sculptor, published by Franz Caramelle in the 1996 Innsbruck exhibition, Ruhm und Sinnlichkeit, highlights a stronger artistic influence from the Flemish sculptor, Alexander Colin (1527 – 1612).

Gras received his initial training as a goldsmith from his father, Egid, in their hometown of Bad Mergentheim, near Würzburg. By the turn of the century he was working with the foremost sculptor of the region, Hubert Gerhard (1540-1620), with whom he moved to Innsbruck in 1602. On 16th June 1609 Gras married Elisabeth Stosseri. When Gerhard’s illustrious career took him to Munich in 1613, Gras assumed the prestigious and lucrative position of court sculptor to Archduke Maximilian III (1558-1618). Thus, he was the principal sculptor responsible for the bronze monument to the Archduke in Innsbruck Cathedral completed in 1619. The intricate design of the armour and the solomonic columns (cast by Heinrich Reinhart) reflects the sculptor’s goldsmith training and anticipates the detailing in his bronze statuettes.

Gras’s first wife died in 1616 leaving him with four children. He married again the following year and had a further ten children with his second wife, Maria Endorfer. Despite a more distant relationship with Archduke Leopold V (1586-1632), who was more reluctant to spend money on the Arts than his predecessor, the following two decades saw Gras’s artistic maturity. During this period, Gras completed his most important and most public commission: the Equestrian statue of Archduke Leopold V, known as the Leopoldsbrunnen (1623-1630). It is important to note that the present nineteenth century configuration is not its original arrangement. The monumental curvetting equestrian group is an extraordinary technical tour de force, and the earliest such ambitious composition in Europe. As discussed below, it directly relates to his bronze statuettes connected to the present Equestrian group of Emperor Ferdinand III of Tyrol.

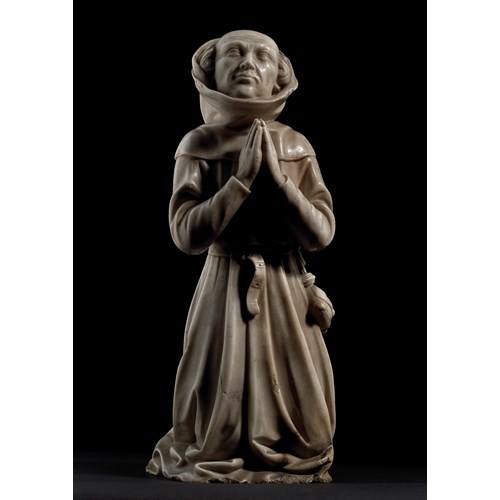

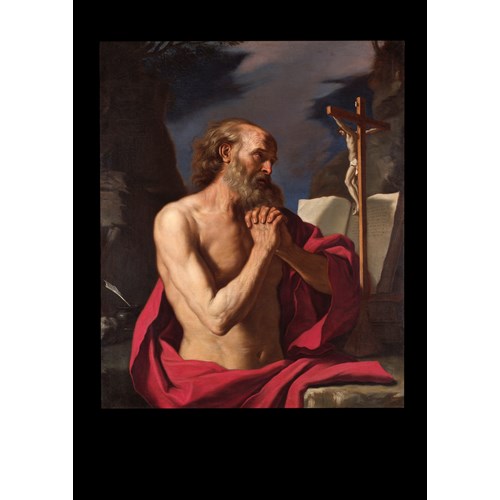

Difficulties completing private commissions and the death of his second wife in 1630 contributed to a decline in Gras’s fortunes that were further exacerbated by even fewer court commissions from Archdukes Ferdinand Karl (1628-1662) and Sigismund Franz (1630-1665) during the troubled period of the Thirty Years’ War. The enduring influence on Gras of the old fashioned style of Alexander Colin is evident in his large-scale commissions, such as in the bronze kneeling figure of Grafen Paul Sixt Trautson (1614) in the church of St. Michael in Vienna - which anticipates his statue of Maximilian III, in the two works he made for Wilten Abbey in Innsbruck: the bronze Giant Haymon (1620) on the facade and the Crucifixion group (1620) inside the Abbey, and later in his wall memorial to Archduke Leopold V and Claudia de’ Medici (1628), made for Schloß Rodeneck. The monumental Virgin and Child (1631), cast by Valentin Algeyer, which today stands high on a column in Münsterplatz, Konstanz, demonstrates how Gras continued to temper the lessons he learnt from Hubert Gerhard with a restrained style influenced by Colin. Gras's last documented large-scale work is the extraordinary bronze Winged Pegasus (1660), cast by Maximilian Röck in 1668, in the garden of Schloß Mirabell, Salzburg, which dramatically reworks the rearing horse of the Leopoldsbrunnen. For Caramelle all the above-mentioned works show how Gras struggled to adapt to the prevailing Baroque style.

With the increasingly intermittent major commissions after the mid-1630s, Gras seems to have focused his activity on small bronzes. The present very fine Equestrian group of Emperor Ferdinand III epitomises Caspar Gras’s development of the bronze statuette tradition. These bronzes give a unique insight into the serialisation of bronzes during the 17th century in the manner in which they are cast with interchangeable heads and accoutrements.

The present bronze belongs to a group of curvetting equestrian statuettes mostly representing members of the Habsburg dynasty, although the identification of each rider is not always obvious. Four of these bronzes are today in the Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna. These depict Emperor Ferdinand III as a youth (inv. 6020), Ferdinand III as an older man (inv. 5989), Leopold I as a youth (inv. 6000), a rider who resembles Archduke Leopold V and Ferdinand II, but is not convincingly either of them (inv. 6025). A fifth bronze of Archduke Ferdinand Karl or Siegmund Franz (inv. 5995) was formerly part of this group.

Outside Vienna there are at least seven other related bronzes. A very fine cast that represents Archduke Ferdinand Karl is in the V&A Museum, London and once formed part of the Vienna group (inv. A16-1960, formerly Kunsthisorisches Museum, inv. 6012), a unique gilt bronze group of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm is in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen (inv. KMS5501), a bronze formerly with Alain Moatti in Paris has been described as the Duc de Vendôme (or maybe Philip IV of Spain), a cast with a variant curvetting horse, whose rider is probably Archduke Ferdinand Karl, sold at Sotheby’s as lot 71 on 7 December 1989. In addition, Leithe-Jasper noted two similar bronzes on curvetting horses in the Galleria Sangiorgi in Rome.

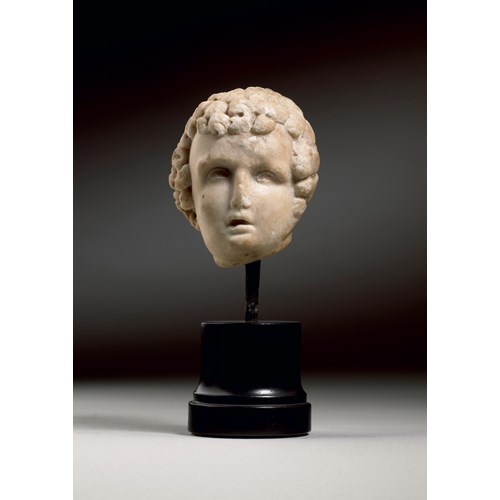

In all these bronzes the model of the horse seems to be so close to one another that they may all have been cast from the same model. On the other hand Leithe-Jasper divided the models of the riders into two main groups and six different types, and each rider has differences in their armour, leading to the conclusion that ‘these figures of horsemen were produced in quantity and kept in store; in all probability the heads were executed last, when it was known who was to be portrayed’. This proposition is supported by the existence of individual heads that could be fitted into a rider when the demand arose.

A separate group of equestrian bronzes has analogous Habsburg and other riders, but their horses are pacing rather than curvetting; these are exemplified by the present excellent cast. Leithe-Jasper discussed these, noting two versions with the Galleria Sangiorgi representing Philip IV of Spain and Emperor Ferdinand III (the latter being the present example). Another with a young horseman is in the Düsseldorf Kunstmuseum (inv. 174 P/B 14). The Innsbruck 1996 exhibition included an equestrian group of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, then newly emerged from a private Tyrolean collection, that can be closely related to these three bronzes. To these can be added a similar but more distant model, thought to represent Archduke Ferdinand Karl, that is known in several casts, best represented by one in the Museo Lazaro Galdiano, Madrid (inv. 145).

Leithe-Jasper has fully rehearsed the arguments in favour of the attribution of the curvetting models to Caspar Gras. These models were first associated with Gras as early as 1742 by Anton Roschmann in relation to an equestrian statuette with interchangeable heads belonging to Count Brandis in Innsbruck. In 1781 two of the Vienna bronzes then in the collection of Josef Angelo de France, the Imperial Treasurer, were catalogued as being by ‘Gasparum Grasium operis artificem suspicetur’. Gras continued to be linked with these bronzes by several nineteenth century commentators.

Interestingly, the question of an alternative to the attribution to Gras arose from the interpretation of small bronzes with interchangeable parts. Julius von Schlosser proposed that the following passage in Baldinucci’s life of Giovanni Francesco Susini (1688) aligned with the Vienna bronzes:

‘Fece più modelli di piccoli cavalli, e talora servissi di quei del Zio [Antonio Susini], e di Giovan Bologna, facendovi sopra le figure co’ ritratti di coloro che gli domandavano, e di sì fatte sue opere mandò in quantità in Lombardia, in Germania, e in Francia a gran prezzi’.

That this passage evokes the Vienna bronzes is clear and the observation that Giovanni Francesco Susini exported these equestrian portrait statuettes to Germany and elsewhere is compelling. It has also been observed that since some of the riders lack the Order of the Golden Fleece (which merit they did in fact hold), implies that Gras could not have done them, because he would have been better informed. This theory was endorsed by Leo Planiscig and Anthony Radcliffe, but since the late 1960s Gras’s authorship has been reinstated by Erich Egg (1960), Hans Robert Weihrauch (1967), Franz Carmelle (1972), Ebba Koch (1975-6), Harald Peter Olsen (1980) and Manfred Leithe-Jasper (in several publications).

The current strong balance of opinion in favour of the attribution of the Habsburg equestrian bronzes to Caspar Gras relies on their evident association with the sculptor’s monumental Equestrian portrait of Archduke Leopold V on the eponymous fountain in Innsbruck. The Tyrolean aristocracy who in all likelihood ordered these bronzes to demonstrate their loyalty to the ruling dynasty would have easily been able to identify their ‘hall monument’ with the public statue completed in 1631. There is no question that Gras’s rearing horse is strongly influenced by Florentine sculpture and depends on the same heritage as Pietro Tacca’s Equestrian portrait of Philip IV of Spain in Madrid, which was completed around a decade later.

Whilst Gras is not recorded as having visited Florence, the marital bonds between the courts in Innsbruck and Florence would have fostered a common aesthetic amongst the sculptor’s Tyrolean patrons. In 1626, Archduke Leopold married Claudia, the daughter of Ferdinando I de’ Medici and in 1646 their son, Ferdinand Karl married Anna, the daughter of Cosimo II de’ Medici. Therefore, a similar taste for domestic-scale bronzes between Innsbruck and Florence is to be expected during this period.

Since it has been shown that the models for the horse and riders remained consistent across the dozen or so known casts, the exact chronology of these bronzes has not been established. However, an argument in favour of the proposition that the pacing horse model pre-dates the corvetting horse is endorsed by the affinity of the former with Hubert Gerhard’s Equestrian statuette of Archduke Maximillian III (1600 – 1605). The stance of the horse in our group attributed to Gras is a mirrored to Gerhard’s model. This differs notably from the tradition of Giambologna’s more powerful pacing horse derived from the Monument to Cosimo I de’ Medici (1594). The cast exhibited in Innsbruck, 1996, cat. 98 is the closest to Gerhard’s model, whilst the ex-Galleria Sangiori casts have longer manes. Although it has been suggested that the inspiration for the corvetting horse could have been Giambologna’s Nessus and Deianara, which dates to 1577, Gras would not have considered this until the commission for the Leopoldsbrunnen in 1623.

The touchstones of Caspar Gras’s oeuvre are his Monument to Maximilian III and the Leopoldsbrunnen. Any assessment and attribution of his small bronzes must be continually referenced to these two magna opera. The idea that the Vienna equestrian statuettes and related casts could be by Giovanni Francesco Susini demonstrates how closely Gras achieved an emulation of the Florentine manner, doubtless to please his patrons’ tastes. However, the fastidious attention to detail in these casts, exemplified by the minute precision in the finishing of the horse’s hooves, stirrups and other accoutrements in the present Equestrian statuette of Emperor Ferdinand III are quite unlike the work of Susini. By contrast they are wholly concordant with the two above-mentioned monuments. Gras lived and worked his whole life in Innsbruck and his corvetting and pacing equestrian statuettes symbolise his devotion and dependence on the patronage of the Habsburg rulers.

Related Literature

M. Leithe-Jasper, Renaissance Master Bronzes from the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, exh. cat., Washington, Los Angeles and Chicago, 1986, pp. 246-253, cats. 66a and 66b

M. Leithe-Jasper, ‘Vier Reiterstatuen’, in Ruhm und Sinnlichkeit. Innsbrucker Bronzeguss 1500-1650. Von Kaiser Maximilian I. bis Erzherzog Ferdinand Karl’, Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, 1996, pp. 302-309

C. Avery, ‘The Bronze Statuettes of Caspar Gras (ca. 1585-1674)’ in Studies in Italian Sculpture, London, 2001, pp. 431-472, figs. 54-56

As in recent years Antonio Susini and Pietro Tacca have emerged from the towering shadow of Giambologna south of the Alps, so too Caspar Gras has increasingly been understood as a distinct and notable artistic personality in relation to Hubert Gerhard north of the Alps. However, whilst recent biographical summaries have focused on Gerhard’s influence on Gras, the most complete biography of the sculptor, published by Franz Caramelle in the 1996 Innsbruck exhibition, Ruhm und Sinnlichkeit, highlights a stronger artistic influence from the Flemish sculptor, Alexander Colin (1527 – 1612).

Gras received his initial training as a goldsmith from his father, Egid, in their hometown of Bad Mergentheim, near Würzburg. By the turn of the century he was working with the foremost sculptor of the region, Hubert Gerhard (1540-1620), with whom he moved to Innsbruck in 1602. On 16th June 1609 Gras married Elisabeth Stosseri. When Gerhard’s illustrious career took him to Munich in 1613, Gras assumed the prestigious and lucrative position of court sculptor to Archduke Maximilian III (1558-1618). Thus, he was the principal sculptor responsible for the bronze monument to the Archduke in Innsbruck Cathedral completed in 1619. The intricate design of the armour and the solomonic columns (cast by Heinrich Reinhart) reflects the sculptor’s goldsmith training and anticipates the detailing in his bronze statuettes.

Gras’s first wife died in 1616 leaving him with four children. He married again the following year and had a further ten children with his second wife, Maria Endorfer. Despite a more distant relationship with Archduke Leopold V (1586-1632), who was more reluctant to spend money on the Arts than his predecessor, the following two decades saw Gras’s artistic maturity. During this period, Gras completed his most important and most public commission: the Equestrian statue of Archduke Leopold V, known as the Leopoldsbrunnen (1623-1630). It is important to note that the present nineteenth century configuration is not its original arrangement. The monumental curvetting equestrian group is an extraordinary technical tour de force, and the earliest such ambitious composition in Europe. As discussed below, it directly relates to his bronze statuettes connected to the present Equestrian group of Emperor Ferdinand III of Tyrol.

Difficulties completing private commissions and the death of his second wife in 1630 contributed to a decline in Gras’s fortunes that were further exacerbated by even fewer court commissions from Archdukes Ferdinand Karl (1628-1662) and Sigismund Franz (1630-1665) during the troubled period of the Thirty Years’ War. The enduring influence on Gras of the old fashioned style of Alexander Colin is evident in his large-scale commissions, such as in the bronze kneeling figure of Grafen Paul Sixt Trautson (1614) in the church of St. Michael in Vienna - which anticipates his statue of Maximilian III, in the two works he made for Wilten Abbey in Innsbruck: the bronze Giant Haymon (1620) on the facade and the Crucifixion group (1620) inside the Abbey, and later in his wall memorial to Archduke Leopold V and Claudia de’ Medici (1628), made for Schloß Rodeneck. The monumental Virgin and Child (1631), cast by Valentin Algeyer, which today stands high on a column in Münsterplatz, Konstanz, demonstrates how Gras continued to temper the lessons he learnt from Hubert Gerhard with a restrained style influenced by Colin. Gras's last documented large-scale work is the extraordinary bronze Winged Pegasus (1660), cast by Maximilian Röck in 1668, in the garden of Schloß Mirabell, Salzburg, which dramatically reworks the rearing horse of the Leopoldsbrunnen. For Caramelle all the above-mentioned works show how Gras struggled to adapt to the prevailing Baroque style.

With the increasingly intermittent major commissions after the mid-1630s, Gras seems to have focused his activity on small bronzes. The present very fine Equestrian group of Emperor Ferdinand III epitomises Caspar Gras’s development of the bronze statuette tradition. These bronzes give a unique insight into the serialisation of bronzes during the 17th century in the manner in which they are cast with interchangeable heads and accoutrements.

The present bronze belongs to a group of curvetting equestrian statuettes mostly representing members of the Habsburg dynasty, although the identification of each rider is not always obvious. Four of these bronzes are today in the Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna. These depict Emperor Ferdinand III as a youth (inv. 6020), Ferdinand III as an older man (inv. 5989), Leopold I as a youth (inv. 6000), a rider who resembles Archduke Leopold V and Ferdinand II, but is not convincingly either of them (inv. 6025). A fifth bronze of Archduke Ferdinand Karl or Siegmund Franz (inv. 5995) was formerly part of this group.

Outside Vienna there are at least seven other related bronzes. A very fine cast that represents Archduke Ferdinand Karl is in the V&A Museum, London and once formed part of the Vienna group (inv. A16-1960, formerly Kunsthisorisches Museum, inv. 6012), a unique gilt bronze group of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm is in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen (inv. KMS5501), a bronze formerly with Alain Moatti in Paris has been described as the Duc de Vendôme (or maybe Philip IV of Spain), a cast with a variant curvetting horse, whose rider is probably Archduke Ferdinand Karl, sold at Sotheby’s as lot 71 on 7 December 1989. In addition, Leithe-Jasper noted two similar bronzes on curvetting horses in the Galleria Sangiorgi in Rome.

In all these bronzes the model of the horse seems to be so close to one another that they may all have been cast from the same model. On the other hand Leithe-Jasper divided the models of the riders into two main groups and six different types, and each rider has differences in their armour, leading to the conclusion that ‘these figures of horsemen were produced in quantity and kept in store; in all probability the heads were executed last, when it was known who was to be portrayed’. This proposition is supported by the existence of individual heads that could be fitted into a rider when the demand arose.

A separate group of equestrian bronzes has analogous Habsburg and other riders, but their horses are pacing rather than curvetting; these are exemplified by the present excellent cast. Leithe-Jasper discussed these, noting two versions with the Galleria Sangiorgi representing Philip IV of Spain and Emperor Ferdinand III (the latter being the present example). Another with a young horseman is in the Düsseldorf Kunstmuseum (inv. 174 P/B 14). The Innsbruck 1996 exhibition included an equestrian group of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, then newly emerged from a private Tyrolean collection, that can be closely related to these three bronzes. To these can be added a similar but more distant model, thought to represent Archduke Ferdinand Karl, that is known in several casts, best represented by one in the Museo Lazaro Galdiano, Madrid (inv. 145).

Leithe-Jasper has fully rehearsed the arguments in favour of the attribution of the curvetting models to Caspar Gras. These models were first associated with Gras as early as 1742 by Anton Roschmann in relation to an equestrian statuette with interchangeable heads belonging to Count Brandis in Innsbruck. In 1781 two of the Vienna bronzes then in the collection of Josef Angelo de France, the Imperial Treasurer, were catalogued as being by ‘Gasparum Grasium operis artificem suspicetur’. Gras continued to be linked with these bronzes by several nineteenth century commentators.

Interestingly, the question of an alternative to the attribution to Gras arose from the interpretation of small bronzes with interchangeable parts. Julius von Schlosser proposed that the following passage in Baldinucci’s life of Giovanni Francesco Susini (1688) aligned with the Vienna bronzes:

‘Fece più modelli di piccoli cavalli, e talora servissi di quei del Zio [Antonio Susini], e di Giovan Bologna, facendovi sopra le figure co’ ritratti di coloro che gli domandavano, e di sì fatte sue opere mandò in quantità in Lombardia, in Germania, e in Francia a gran prezzi’.

That this passage evokes the Vienna bronzes is clear and the observation that Giovanni Francesco Susini exported these equestrian portrait statuettes to Germany and elsewhere is compelling. It has also been observed that since some of the riders lack the Order of the Golden Fleece (which merit they did in fact hold), implies that Gras could not have done them, because he would have been better informed. This theory was endorsed by Leo Planiscig and Anthony Radcliffe, but since the late 1960s Gras’s authorship has been reinstated by Erich Egg (1960), Hans Robert Weihrauch (1967), Franz Carmelle (1972), Ebba Koch (1975-6), Harald Peter Olsen (1980) and Manfred Leithe-Jasper (in several publications).

The current strong balance of opinion in favour of the attribution of the Habsburg equestrian bronzes to Caspar Gras relies on their evident association with the sculptor’s monumental Equestrian portrait of Archduke Leopold V on the eponymous fountain in Innsbruck. The Tyrolean aristocracy who in all likelihood ordered these bronzes to demonstrate their loyalty to the ruling dynasty would have easily been able to identify their ‘hall monument’ with the public statue completed in 1631. There is no question that Gras’s rearing horse is strongly influenced by Florentine sculpture and depends on the same heritage as Pietro Tacca’s Equestrian portrait of Philip IV of Spain in Madrid, which was completed around a decade later.

Whilst Gras is not recorded as having visited Florence, the marital bonds between the courts in Innsbruck and Florence would have fostered a common aesthetic amongst the sculptor’s Tyrolean patrons. In 1626, Archduke Leopold married Claudia, the daughter of Ferdinando I de’ Medici and in 1646 their son, Ferdinand Karl married Anna, the daughter of Cosimo II de’ Medici. Therefore, a similar taste for domestic-scale bronzes between Innsbruck and Florence is to be expected during this period.

Since it has been shown that the models for the horse and riders remained consistent across the dozen or so known casts, the exact chronology of these bronzes has not been established. However, an argument in favour of the proposition that the pacing horse model pre-dates the corvetting horse is endorsed by the affinity of the former with Hubert Gerhard’s Equestrian statuette of Archduke Maximillian III (1600 – 1605). The stance of the horse in our group attributed to Gras is a mirrored to Gerhard’s model. This differs notably from the tradition of Giambologna’s more powerful pacing horse derived from the Monument to Cosimo I de’ Medici (1594). The cast exhibited in Innsbruck, 1996, cat. 98 is the closest to Gerhard’s model, whilst the ex-Galleria Sangiori casts have longer manes. Although it has been suggested that the inspiration for the corvetting horse could have been Giambologna’s Nessus and Deianara, which dates to 1577, Gras would not have considered this until the commission for the Leopoldsbrunnen in 1623.

The touchstones of Caspar Gras’s oeuvre are his Monument to Maximilian III and the Leopoldsbrunnen. Any assessment and attribution of his small bronzes must be continually referenced to these two magna opera. The idea that the Vienna equestrian statuettes and related casts could be by Giovanni Francesco Susini demonstrates how closely Gras achieved an emulation of the Florentine manner, doubtless to please his patrons’ tastes. However, the fastidious attention to detail in these casts, exemplified by the minute precision in the finishing of the horse’s hooves, stirrups and other accoutrements in the present Equestrian statuette of Emperor Ferdinand III are quite unlike the work of Susini. By contrast they are wholly concordant with the two above-mentioned monuments. Gras lived and worked his whole life in Innsbruck and his corvetting and pacing equestrian statuettes symbolise his devotion and dependence on the patronage of the Habsburg rulers.

Related Literature

M. Leithe-Jasper, Renaissance Master Bronzes from the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, exh. cat., Washington, Los Angeles and Chicago, 1986, pp. 246-253, cats. 66a and 66b

M. Leithe-Jasper, ‘Vier Reiterstatuen’, in Ruhm und Sinnlichkeit. Innsbrucker Bronzeguss 1500-1650. Von Kaiser Maximilian I. bis Erzherzog Ferdinand Karl’, Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, 1996, pp. 302-309

C. Avery, ‘The Bronze Statuettes of Caspar Gras (ca. 1585-1674)’ in Studies in Italian Sculpture, London, 2001, pp. 431-472, figs. 54-56

Medium: Bronze

Signature: 30 x 28.5 cm (11 ¾ x 11 ¼ in.), 39.5 cm (15 ½ in.) high overall

Provenance: Galleria Sangiorgi, Rome c. 1900

Sotheby’s London, 12th April 1990, lot 53

Private collection, France

More artworks from the Gallery

-13. Equestrian Statue of Emperor Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (1608 – 1657)_T639063393011638729.jpg?width=2000&height=2000&mode=max&scale=both&qlt=90)