Marketplace

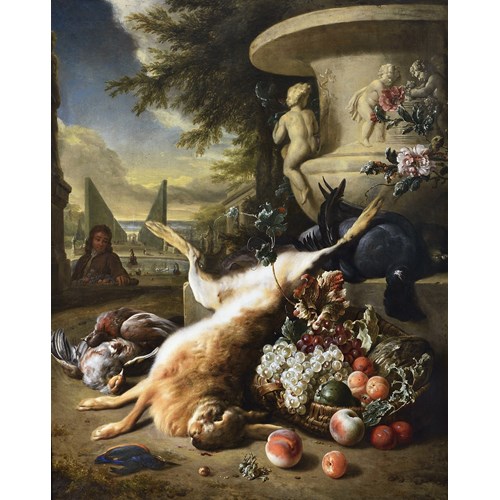

“An Arcadian Landscape with stories from the legends of Pan and Bacchus”

NICOLAS POUSSIN

“An Arcadian Landscape with stories from the legends of Pan and Bacchus”

Date 1625

Epoque 1600-1750, 17th century

Origine Italy, France

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimension 73.6 x 95.6 cm (29 x 37⁵/₈ inches)

The whereabouts of this picture remained unknown until brought to Christie’s, London, in 1894 by Mr. Arthur Whitcombe of 11 Clarence Street, Cheltenham. The work was recorded at the auction house—he brought in 3 pictures on 8 May 1894—but none offered for sale at that time and they were returned to Mr. Whitcombe. The painting has resurfaced again only recently.

It should not be surprising that Poussin included so many different stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses in this one composition, given the young Poussin’s interest in poetry, no doubt stemming from the influence of one of his first protectors, namely the Italian poet Giambattista Marino (1569-1625), who considered himself a disciple of the Latin poet. In fact, it is the subtle Ovidian eroticism lurking beneath Marino’s poetry that serves as the key to understanding the seemingly irrational arrangement of mythological figures strewn across the fictive Arcadia.

Poussin takes as his setting this fabled land where Pan guarded flocks, herds and bee-hives, where Pan took part in the revels of the mountain nymphs—seducing many of them—and where Pan helped hunters to find their quarry. To the upper right of this landscape, one satyr stands in anticipation as another passes down the harvest; at the base of a tree rests a youth watching the gathering. In the middle of the composition, Pan has succeeded in capturing the chaste Syrinx after pursuing her all the way from Mount Lycaeum to the river Ladon, personified by the river god to their left (Ovid, Metamorphosis, 1:689 – 713). Praying to be transformed, Syrinx becomes a reed, and since Pan could not distinguish her from those growing near the river shore, he cut several at random and made the reeds into a pipe.

Attempts to explain the gathering of figures in the foreground is more difficult. Crowned Midas in his golden robe rests his head with his right hand as his listens to Pan sound his pipe. To his left may be the infant Satyr whose intense gaze at the poppies alludes to the sleep inducing power associated with the flower. Below Pan and slightly behind rests a youth while two figures to Pan’s left appear mesmerized by his playing, perhaps Alpheus and Arethusa, another variant of the Pan and Syrinx story: returning from the hunt one day Arethusa, one of Diana’s attendants, bathes in the river Alpheus where the god of the river becomes so enamored of her that he pursues the beautiful bather. She implores Diana for help and is turned into a fountain. The tragedy that lies before all of these figures—both in the foreground and middle distance—may be the connective issue: Syrinx will become a mere reed, the infant Satyr may forever be bound to an interminable dream, Midas’s touch will cause him almost interminable hunger and thirst, Pan will be scourged with quills containing irritant poisons, and Alpheius and Arethusa respectively will be turned into a river and spring. Would it not be, as Poussin might have intended to say in this mute elegy, that tragedy resides in Arcadia as it does in the present world? Quite possibly, the picture might have been conceived as one of a pair of pictures, with contrasting musical themes. The pendants might have presented the two choices put to Midas, with the present work exploring the base music of the reed pipe that Pan played, while the other picture would have depicted the heavenly music played by Apollo on the lyre. Midas’s disastrous choice of Pan over Apollo and his resulting affliction would be perfectly in keeping with the tone of much of the poetry written in the intellectual circles around the young Poussin.

Sir Denis Mahon has dated his painting to circa 1625, a year in which Poussin had a persistent need for income due to the death of the poet Giambattista Marino, and the frequent absences of two other protectors of the artist, Cassiano dal Pozzo and Cardinal Francesco Barberini. Mahon holds that this dire financial period for the artist was in part alleviated by the Genoese picture dealer Giovanni Stafano Roccatagliata, to whom he supplied many of these landscapes with nudes and Arcadian themes. Whether or not the present picture was one such picture is impossible to say at this time; however, the circumstances of its production and resultant character are not unrelated to these factors.

For one, the painting shares many similarities with such early works that appear to have been executed for quick sale such as Apollo and Daphne and the Death of Eurydice (private collection), the Landscape with a sleeping Satyr and the Landscape from Grottaferrata of 1626 (both Musee Fabre, Montpelier), the Landscape with Nymphs and Satyrs (Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, no. 1313), and especially the Numa Pompilius et la nymphe Egerie (Chantilly, Musée Conde, inv.129/301). Moreover, many of the small-scale renderings strewn across this composition are mirrored in like pictures painted during his early years. Midas recalls the king of Phrygia in Midas at the source of the Pactolus (1926/27; Musée Fesch, Adaccio). The male figure, wreathed in ivy, climbing up a tree and reaching out for an overhanging bunch of grapes, repeats the otherwise mysterious figure in the Landscape with Bacchus and Ceres of circa 1626 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). This was also the moment when Poussin was most deeply influenced by Venetian painting and in particular quite responsive to the d’Este Bacchanals then in the Aldobrandini collection in Rome. Poussin’s use of warm Venetian tones, his sensitivity to the effects of light and shade on form and color, and his sensual treatment of mythological themes are clearly inspired by his knowledge of Titian’s work.

Poussin’s early works are especially redolent of his youthful personality: collectively they display stock motifs and similar palettes, and have a tendency to follow certain patterns of painting formulated during his first years in Rome. It seems to me that he would first apply a dark ground, either of terra cotta or maroon, and then build up figurative elements with additions of buff, cream, ochre, or patches of blue, and finally establish the highlights with whites. We now know, in fact, that he painted many of these works rapidly, and much of the terracotta hued ground frequently shows through the paint surface.

An Arcadian Landscape with Stories from the Legends of Pan and Bacchus is but one of the more complex attempts by the young artist to perfect his visual rhetoric, and one that serves as a brilliant harbinger of that which we know follows.

Timothy J. Standring

Chief Curator

Denver Art Museum

It should not be surprising that Poussin included so many different stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses in this one composition, given the young Poussin’s interest in poetry, no doubt stemming from the influence of one of his first protectors, namely the Italian poet Giambattista Marino (1569-1625), who considered himself a disciple of the Latin poet. In fact, it is the subtle Ovidian eroticism lurking beneath Marino’s poetry that serves as the key to understanding the seemingly irrational arrangement of mythological figures strewn across the fictive Arcadia.

Poussin takes as his setting this fabled land where Pan guarded flocks, herds and bee-hives, where Pan took part in the revels of the mountain nymphs—seducing many of them—and where Pan helped hunters to find their quarry. To the upper right of this landscape, one satyr stands in anticipation as another passes down the harvest; at the base of a tree rests a youth watching the gathering. In the middle of the composition, Pan has succeeded in capturing the chaste Syrinx after pursuing her all the way from Mount Lycaeum to the river Ladon, personified by the river god to their left (Ovid, Metamorphosis, 1:689 – 713). Praying to be transformed, Syrinx becomes a reed, and since Pan could not distinguish her from those growing near the river shore, he cut several at random and made the reeds into a pipe.

Attempts to explain the gathering of figures in the foreground is more difficult. Crowned Midas in his golden robe rests his head with his right hand as his listens to Pan sound his pipe. To his left may be the infant Satyr whose intense gaze at the poppies alludes to the sleep inducing power associated with the flower. Below Pan and slightly behind rests a youth while two figures to Pan’s left appear mesmerized by his playing, perhaps Alpheus and Arethusa, another variant of the Pan and Syrinx story: returning from the hunt one day Arethusa, one of Diana’s attendants, bathes in the river Alpheus where the god of the river becomes so enamored of her that he pursues the beautiful bather. She implores Diana for help and is turned into a fountain. The tragedy that lies before all of these figures—both in the foreground and middle distance—may be the connective issue: Syrinx will become a mere reed, the infant Satyr may forever be bound to an interminable dream, Midas’s touch will cause him almost interminable hunger and thirst, Pan will be scourged with quills containing irritant poisons, and Alpheius and Arethusa respectively will be turned into a river and spring. Would it not be, as Poussin might have intended to say in this mute elegy, that tragedy resides in Arcadia as it does in the present world? Quite possibly, the picture might have been conceived as one of a pair of pictures, with contrasting musical themes. The pendants might have presented the two choices put to Midas, with the present work exploring the base music of the reed pipe that Pan played, while the other picture would have depicted the heavenly music played by Apollo on the lyre. Midas’s disastrous choice of Pan over Apollo and his resulting affliction would be perfectly in keeping with the tone of much of the poetry written in the intellectual circles around the young Poussin.

Sir Denis Mahon has dated his painting to circa 1625, a year in which Poussin had a persistent need for income due to the death of the poet Giambattista Marino, and the frequent absences of two other protectors of the artist, Cassiano dal Pozzo and Cardinal Francesco Barberini. Mahon holds that this dire financial period for the artist was in part alleviated by the Genoese picture dealer Giovanni Stafano Roccatagliata, to whom he supplied many of these landscapes with nudes and Arcadian themes. Whether or not the present picture was one such picture is impossible to say at this time; however, the circumstances of its production and resultant character are not unrelated to these factors.

For one, the painting shares many similarities with such early works that appear to have been executed for quick sale such as Apollo and Daphne and the Death of Eurydice (private collection), the Landscape with a sleeping Satyr and the Landscape from Grottaferrata of 1626 (both Musee Fabre, Montpelier), the Landscape with Nymphs and Satyrs (Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, no. 1313), and especially the Numa Pompilius et la nymphe Egerie (Chantilly, Musée Conde, inv.129/301). Moreover, many of the small-scale renderings strewn across this composition are mirrored in like pictures painted during his early years. Midas recalls the king of Phrygia in Midas at the source of the Pactolus (1926/27; Musée Fesch, Adaccio). The male figure, wreathed in ivy, climbing up a tree and reaching out for an overhanging bunch of grapes, repeats the otherwise mysterious figure in the Landscape with Bacchus and Ceres of circa 1626 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). This was also the moment when Poussin was most deeply influenced by Venetian painting and in particular quite responsive to the d’Este Bacchanals then in the Aldobrandini collection in Rome. Poussin’s use of warm Venetian tones, his sensitivity to the effects of light and shade on form and color, and his sensual treatment of mythological themes are clearly inspired by his knowledge of Titian’s work.

Poussin’s early works are especially redolent of his youthful personality: collectively they display stock motifs and similar palettes, and have a tendency to follow certain patterns of painting formulated during his first years in Rome. It seems to me that he would first apply a dark ground, either of terra cotta or maroon, and then build up figurative elements with additions of buff, cream, ochre, or patches of blue, and finally establish the highlights with whites. We now know, in fact, that he painted many of these works rapidly, and much of the terracotta hued ground frequently shows through the paint surface.

An Arcadian Landscape with Stories from the Legends of Pan and Bacchus is but one of the more complex attempts by the young artist to perfect his visual rhetoric, and one that serves as a brilliant harbinger of that which we know follows.

Timothy J. Standring

Chief Curator

Denver Art Museum

Date: 1625

Epoque: 1600-1750, 17th century

Origine: Italy, France

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimension: 73.6 x 95.6 cm (29 x 37⁵/₈ inches)

Provenance: Rome, perhaps Stefano Roccatagliata, Cassiano dal Pozzo or another member of his circle;

Arthur Whitcombe, Cheltenham, England;

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie