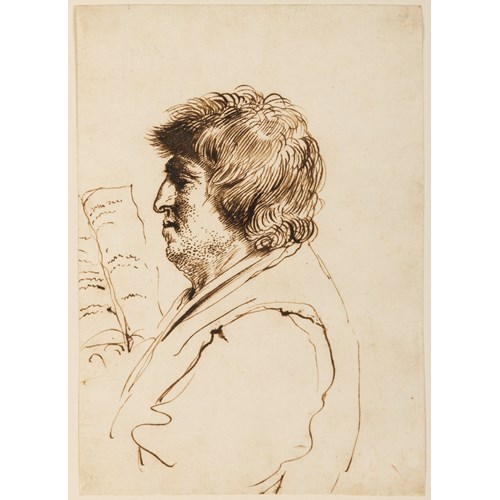

Throughout his life, Ruskin was particularly interested in studying the sky at dawn and at sunset, and habitually woke early in order to see the dawn. Soon after he settled at Brantwood on the lake of Coniston Water in Cumbria in 1871 he had a turret window built at the house so that he could more easily study the sunrise. As he advised his audience, in one of a series of lectures given between 1857 and 1859, ‘Rise early, always watch the sunrise, and the way the clouds break from the dawn’, while several years later, as part of a series of aphorisms, he wrote, ‘Never, if you can help it, miss seeing the sunset and the dawn. And never, if you can help it, see anything but dreams between them.’ Similarly, in his notes accompanying the Educational Series of his own drawings that were presented to the University of Oxford and intended for the instruction of undergraduates, Ruskin added, ‘I would request any student, who finds by the pleasure he takes in colour that he has the right to hope his time will not be wasted in cultivating his gift for it, to set aside a quarter of an hour of every morning, as a part of its devotions, for the observance of the sun-rise, and always to have pencil and colour at hand to make note of anything more than usually beautiful. He will find his thoughts during the rest of the day both calmed and purified, and his advance in all essential art-skill at once facilitated and chastised; quickened by the precision of the exercise, and chastised by the necessity of restraining great part of the field of colour into altogether subdued tones for the sake of parts centrally luminous.’

Paul Walton has noted of Ruskin’s watercolours of sunrises and sunsets that ‘Throughout his life he made careful notes of such occasions in his diary or sketch book…They were all specimens of what he regarded as the divine gift of colour in its purest and most subtle forms.’ As another writer has pointed out of Ruskin, ‘what he takes to heart…is what he had long before perceived in art and literature: that sunrise and sunset mean the same. In Modern Painters V red is the colour of both, and of mortality: “The rose of dawn and sunset is the hue of the rays passing close to the earth. It is also concentrated in the blood of man.”’

Watercolours such as the present sheet also reflect something of the profound and lifelong influence on Ruskin of the work of J. M. W. Turner, whose treatment of skies is mentioned in the younger artist’s writings and correspondence. It is with reference to such atmospheric studies as this that Christopher Newall has written, ‘Drawings of this kind demonstrate a conscious or instinctive debt to the type of colour studies of coastal or lake landscapes that J. M. W. Turner had made in the 1830s and 1840s, of which Ruskin had a number of examples in his collection…In Turner’s views, clouds frequently mask the sun with vaporous atmosphere tinged with reds and blues. Higher in the sky, bars or flecks of cloud catch the sunlight and show as pink strata in the wider cloudscape. Turner’s very personal watercolours of the rising or setting sun exemplify an instinctive response to meteorological phenomena and qualities of atmosphere and light that Ruskin found thrilling to look at and that he consciously or unconsciously imitated.’

The present sheet may be likened to a number of watercolour studies of skies at dawn or sunset by Ruskin. These include Sunset at Herne Hill through the Smoke of London, drawn in 1876, in the Ruskin Museum in Coniston, and Dawn at Neuchâtel, dated 1866, in the collection of David Thomson. Also comparable are a Sunrise over the Sea in the Abbot Hall Art Gallery in Kendal and Sunrise, Vevey in the Alpine Club collection in London, as well as a pair of watercolours of a Study of Dawn: The First Scarlet on the Clouds and a Study of Dawn: Purple Clouds, both drawn in 1868, in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

This fine watercolour probably belonged to Mary Constance (‘Connie’) Hilliard (1852-1915), one of Ruskin’s closest female friends in his middle and later years. The niece of his friend Pauline, Lady Trevelyan, Connie Hilliard first met Ruskin in August 1863 at Wallington, the Trevelyan estate in Northumberland, when she was eleven years old, at a tea party organized by the young girl. Ruskin became very fond of her and in later years Connie and her mother accompanied Ruskin on trips through France, Italy and Switzerland, while her younger brother Laurence Hilliard served as Ruskin’s secretary at Brantwood. In 1880 Connie Hilliard married the Reverend William Henry Churchill (1855-1936), headmaster of St. David’s School in Reigate. Ruskin served as godfather to one of their sons, probably Arnold Churchill (1886-1964), who later inherited the present sheet. A few years after Connie Hilliard’s death, this watercolour was lent by her widowed husband W. H. Churchill to the Ruskin Centenary Exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1919.

Provenance: Probably Mary Constance (‘Connie’) Hilliard (Mrs. W. H. Churchill), and by descent to her son Arnold Churchill, Norwich

Thence by descent to Anthony Churchill Dale, Wiltshire

His sale (‘The Property of Anthony Churchill Dale, Esq.’), London, Christie’s, 18 March 1980, lot 118

Harold and Nicolette Wernick, Springfield, Massachusetts and Bloomfield, Connecticut

Her sale (‘The Nicolette Wernick Collection: British Watercolours & Paintings (1800-1950)’), London, Christie’s, 16 June 2010, lot 81

Private collection.

Literature: London, Royal Academy, Catalogue of the Ruskin Centenary Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, 1919, p.32, no.337 (‘Sunset’); London, Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, John Ruskin (1819-1900): Drawings and Watercolours from a Private Collection, exhibition catalogue, 2024, pp.56-57, no.42.

Exhibition: London, Royal Academy, Ruskin Centenary Exhibition, 1919, no.337 (‘Sunset’, lent by the Rev. W. H. Churchill); Springfield, Massachusetts, George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, 19th Century English Art from the Collection of Harold and Nicolette Wernick, 1988, no.35; London, Guy Peppiatt Fine Art Ltd., John Ruskin (1819-1900): Drawings and Watercolours from a Private Collection, 2024, no.42.

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie