Marketplace

5. Portrait Bust of Roman Empress Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla (c. 150 – 182 A.D.)

5. Portrait Bust of Roman Empress Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla (c. 150 – 182 A.D.)

Medium Marble

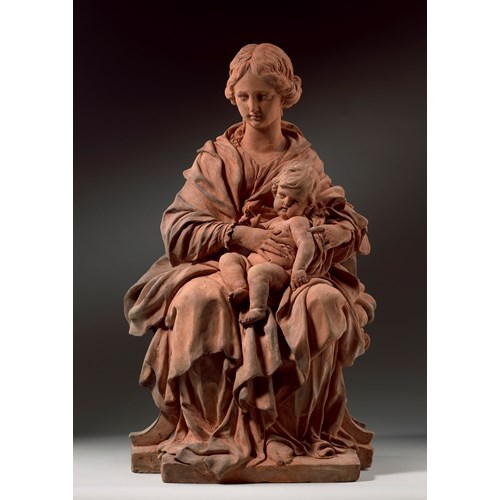

This life-size and sensitively carved portrait of a woman with plump features, prominent incised eyes and deeply waved hair tied into a low bun embodies the standards of female beauty and imperial iconography of the mid-Antonine period, around 150–70 A.D. The Antonine dynasty began with the reign of Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161 A.D.), continued through those of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 A.D.) and his co-regent Lucius Verus (r. 161–169 A.D.), and ended with the assassination of Commodus (r. 177–192 A.D.). Thanks to her distinctive physiognomy, the present sitter can be identified as Lucilla, one of the daughters of Emperor Marcus Aurelius and his wife Faustina the Younger (130–175 A.D.). Born in about 150 A.D., Lucilla married her father's adoptive brother Lucius Verus in 164 A.D., upon which occasion she received the title of ‘Augusta’ and was crowned empress. Her tenure as imperial consort was short-lived, and when her husband died in 169 A.D., she was married again to another of her father’s political allies, a consul from Syria. After her brother Commodus ascended the throne in 177 A.D. and his behaviour started to undermine the stability of government, Lucilla joined a conspiracy to have him assassinated. As the plot failed, she was exiled to Capri and eventually executed in 182 A.D.

In terms of iconography, the present bust shows clear parallels with portraits of Lucilla’s mother Faustina the Younger. Not merely an expression of their biological kinship, these parallels were the result of a systematic approach to portraiture as a means of establishing the genealogical unity of the ruling family and the role of the emperor's wife in perpetuating the dynasty thanks to her fecunditas (“fertility”). The first scholar to propose a classification of the portraits of Faustina the Younger and Lucilla in the twentieth century was German archaeologist Max Wegner (1902-1998), whose typological approach was reprised and developed by Professor Klaus Fittschen (b. 1936) in a 1982 study dedicated solely to the likenesses of these two imperial women (see Related Literature). Analysing coins and statues, Fittschen identified nine types of Faustina’s portrait and posited that each was created to coincide with one of her pregnancies, a formula that he suggested was repeated for Lucilla and her three children, underscoring the centrality of fertility in relation to the image of Roman imperial women. Specifically, Fittschen described a “fifth type”, dateable to the birth of Faustina’s son Tiberius Aelius Antoninus in 152 A.D., as characterised by a rounded head and plump features, a slightly aquiline nose, large eyes, and uniformly wavy hair tied in a bun at the nape of the neck. As the German scholar explains, the fifth type of Faustina’s portrait formed the basis for one of the three types of portrait of Lucilla he codifies, exemplified by the present bust and known in four other variants: in Dresden (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Skulpturensammlung, inv. no. Hm 394, figs. 3a-d); in Rome (Musei Capitolini, inv. no. 1781, fig. 4); in Berlin (Staatliche Museen, Antikensammlung, inv. no. Sk 446, fig. 5); and in Tripoli (Archeological Museum, fig. 6). According to Fittschen, this type was likely devised in conjunction with Lucilla’s second pregnancy in 166 A.D., and the key to distinguishing between mother and daughter rests in the greater accentuation of the wave pattern found in Lucilla’s hair, as seen here and in the aforementioned variants (figs. 3-6). A deep wave pattern is also found in portraits of Faustina, but of the seventh type, where the hair is divided clearly into strands and braids, unlike in the present case.

One characteristic unique to the present likeness across the portraiture of Lucilla is the conformation of its bust, which includes the sitter’s right arm and hand emerging from her robes. Often found in full-length statues of Roman matrons, this arrangement is less frequent in busts and as such represents a key element towards tracing the history of our portrait. Inventorial records of ancient busts – especially female ones – in early-modern Europe are usually highly generic, with descriptions ranging from a simple name to even more broad definitions, such as “Head of a woman”. More specific evidence can, however, be provided by the existence of period copies, and in the case of the present bust five have been identified, dating to the seventeenth century.

The first one to consider is a bronze bust which has remained in the Royal Collection, since the reign of Charles I. The bust can be identified in the third group of drawings in the ‘Whitehall album’, which are thought to illustrate busts that were at Whitehall at the time of the Restoration.

The second is a plaster cast located over a doorframe on the Great Staircase of Ham House on the River Thames, which can be dated on the basis on documentary evidence to between about 1637 and 1672. Erected in 1610 by courtier Thomas Vavasour, in 1626 Ham House was leased and then bought by William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart – a close ally of King Charles I – who extended and embellished the existing building. After the family lost ownership of the house during the Civil War, the Earl’s eldest daughter Elizabeth acquired it back in 1650 and settled there with her first husband, Sir Lionel Tollemache. Following the latter’s death in 1669, Elizabeth married John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, in 1672, and together they set about enlarging and redecorating the house. Part of their renovations included work on the Great Staircase, executed in 1671-72 by one John Burnell, as recorded in a payment to him “Ffor severall Jobbs about ye house & cutting of holes in ye starecase for ye heads to stand in, & helping them up”. The heads mentioned in this entry correspond to the “4 heades of plaster” and “4 Marble Heads” listed in the same location in the 1677 inventory of Ham House, with the plaster ones – including the copy of the present Lucilla – visible in situ to this day. As Charles Avery argues in his analysis of the seventeenth century sculpture at Ham House, the plasters were probably executed by members of the Besniers émigré family of sculptors, who were active in London through most of the seventeenth century and arrived from France, perhaps as part of the retinue of Queen Henrietta Maria around 1625. During the Restoration, the Besniers were “involved specifically in the business of making casts in base materials, either directly after the Antique or from Le Sueur's earlier, royal copies”, which survived in their possession. However – Avery continues – “it is most likely that the plaster busts after the Antique were already in situ between the broken pediments of the Great Staircase as part of William Murray's classicising scheme of decoration, c. 1637-9. In that case, they could even have been cast by Isaac Besnier, who was available in London until 1643.”

Avery therefore dates the execution of the Ham House plaster copy of the present Lucilla to between c. 1637 and 1672, which is also the likely period of execution of another copy, in bronze, visible today on the entrance door of William III’s Little Banqueting House at Hampton Court. Not much is known about this version or how it became an integral part of the architecture at Hampton Court, but the Little Banqueting House was built in 1700, which offers a likely terminus ante quem for the casting of the bronze (assuming it is original to the building). The Besniers’ activity as court sculptors to Charles I and Charles II constitutes the most plausible explanation for this cast being part of a royal residence and also establishes a link with the plaster at Ham House, which is confirmed by the fact that these two copies appear to derive from the same mould, with very slight differences from the present marble noticeable in the folds of the drapery.

A third bust associated to the present portrait is at Wilton House in Wiltshire, home of the famous collection of sculpture assembled by Thomas Herbert, 8th Earl of Pembroke, in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Carved in marble, this bust was first recorded at Wilton in the manuscript catalogues of circa 1732 and Peter Stewart, who has compiled the recent catalogue raisonné of the sculpture at Wilton House, considers it a work of the first half of the seventeenth century, carved after the present prototype. Its facial features depart somewhat from those of our Lucilla, with more generic traits and blank pupils, but the structure of the bust, the appearance of the hair and the arrangement of the drapery are all closely comparable, confirming a direct link between the two busts. Further evidence of this connection is offered by comparison on the tabula of the socles of the two busts, each ornamented with frolicking putti, although they differ somewhat in representations of the puttis cavorting. This type of socle is ancient and can be found in a limited number of Roman portraits existing today, as will be discussed below. In terms of provenance, Stewart specifies that the Wilton bust – believed to be a portrait of Didia Clara by the 8th Earl, a name still associated with it – had probably been obtained from a Parisian source, possibly the collection of Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661), which Pembroke is documented to have acquired pieces from. Notably, Stewart adds that the present bust “may itself have been in the Mazarin collection”.

Among the most powerful politicians of the seventeenth century, Mazarin rose through the ranks of the French court to become chief minister to Louis XIII and Louis XIV, and in the process assembled one of the most illustrious collections of antiquities of the age, which was dispersed gradually by his descendants. Inventories of the Cardinal’s collection offer predominantly a general nomenclature of the statues, such as “Head of an Empress with Bust”, with several descriptions repeated more than once, making it difficult to securely trace the whereabouts of many of the items. The link with France proposed by Stewart, however, is undoubted, as the fourth copy of the present bust dateable to the seventeenth century – and the most accurate and highly finished one – is today in the Salon de l’Abondance at Versailles. Not part of the palace’s original decoration, this bronze is from the collection of the Louvre, and whilst no information has been published on its provenance, it is dated to the seventeenth century on stylistic grounds, and its facture and colour suggest it was cast in France. Now named “Poppaea Sabina”, possibly because it forms a pair with a bust of the eponymous Roman matron’s husband Nero, the Versailles bronze was previously titled “Faustina the Younger”.

It is worth pointing out here that a bust of Nero of the same type as the Versailles pair to the “Poppaea Sabina” – but in marble – can be found at Wilton House, which underlines that a connection most likely existed between the prototypes of these two portraits in the seventeenth century. This theory is reinforced by the fact that the Wilton Nero is set on a socle with frolicking putti, of the same shape and style as the ones that support the Wilton Didia Clara and the present Lucilla. Highly distinctive and rare, this type of socle has been recorded – with variations in the activities of the putti – in six additional busts: a Portrait of Trajan also at Wilton, but in very compromised condition; a Bust of Semiramis formerly at Wilton and only known through an engraving; an early Antonine period Portrait of a Young Man at Castle Howard; a mid-Antonine period Memorial Bust of a Girl at Petworth; a Portrait of Iulia Domna formerly in the collection of Frederick the Great of Prussia; and a headless Bust of a Youth in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Amongst these, the Portrait of a Young Man at Castle Howard and the Memorial Bust of a Girl at Petworth – which are catalogued as ancient by scholars and dated to the Antonine period – show a treatment of the back of the bust that is closely comparable to that in the present marble, further evidence of its dating to the 2nd century A.D. Presumably, the three busts were carved in the same workshop, which specialised in this type of ornamented socle. The Wilton Trajan is very weathered – Stewart believes its bust to be later than the head – while the Semiramis and the Iulia Domna are untraced, and the headless Youth in Istanbul has not been studied, but photographs of it and its provenance suggest it is indeed ancient. With regards to the seventeenth-century Nero and Didia Clara at Wilton, their socles are not integral to the busts and were likely adapted from earlier statues, perhaps damaged and discarded, or copied from ancient examples.

Having established that, at least by the seventeenth century, the present bust of Lucilla – otherwise identified as Faustina because of the aforementioned similarities between the portraits of these two empresses – was paired with an ancient and currently untraced portrait of Nero, and that the two were documented in France and England, more detailed hypotheses can be put forward regarding their provenance. Peter Stewart was the first to point out that the present bust may well have formed part of the collection of Cardinal Mazarin, a theory supported by the existence of the very fine, French seventeenth-century bronze copy of it in the Louvre. In the context of seventeenth-century collecting in France, a letter sent to Cardinal Mazarin in May 1653 by his agent in London, Monsieur de Bordeaux, stands out. The latter assured his patron that “many busts” could be found in the English capital – then in the chaotic aftermath of the Civil War, when aristocratic collections were being dispersed – and in a list of the ones he considered of the highest quality, de Bordeaux mentioned a Nero and a Faustina (without specifying whether it was the Elder or the Younger Faustina) in marble, “chez M. Guildorphe”, a francophone transliteration of the surname of George Geldorp (1580/95–1665), the painter and art dealer active in England between the reigns of Charles I and Charles II. Unfortunately, subsequent letters between Mazarin and his London agent do not explicitly name these busts again, and the Cardinal cryptically replied to de Bordeaux “As for statues and busts, I do not think we should consider it, since there aren't any so old that we couldn't find one of the same age when we wanted”. This, however, does not exclude the possibility that de Bordeaux ultimately found a French buyer for the busts, or that, even if he did not, he or Geldorp had casts taken of them, which then found their way to France and resulted in the bronzes now at Versailles. Where Geldorp might have sourced the busts of Nero and Faustina has not been possible to determine, but as the collections of antiquities assembled by Thomas, 14th Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), and George, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) demonstrate, an appetite for ancient busts – which would flourish during the era of the Grand Tour – was already established in England in the first half of the seventeenth century. For example, busts of Nero and Faustina are recorded in the 1635 inventory of Buckingham’s suburban villa, Chelsea House, in the long gallery. Within a decade, as the political climate worsened for royalists, his son, the 2nd Duke, began selling off pieces from the collection, which was ultimately entirely dispersed. After the Restoration, English collectors and agents reinstated ties with Italian dealers and restorers in ancient marbles, especially based in Rome, where it is highly likely the present portrait had originally been discovered, and copied by a sculptor whose work – the so-called “Didia Clara” – subsequently made its way to Wilton House.

In the twentieth century, the present bust was owned by Arnold Machin (1911-1999), a sculptor and graphic designer famous for creating the profile portrait of Queen Elizabeth II for the decimal coinage introduced across the Commonwealth in 1968, and that for British postage stamps first issued in 1967.

Related Literature

J. Kennedy, A description of the antiquities and curiosities in Wilton-House. Illustrated with twenty-five engravings of some of the capital statues, bustos and relievos, London, 1769

M. Wegner, Das römische Herrscherbild: Die Herrscherbildnisse in antoninischer Zeit, vol. 4, section II, Berlin, 1939

K. Fittschen, Die Bildnistypen der Faustina Minor und die Fecunditas Augustae (Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Philologisch-historische Klasse, Dritte Folge CXXVI), Göttingen, 1982

K. Fittschen and P. Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts in den Capitolinischen Museen und den anderen Kommunalen Sammlungen der Stadt Rom III: Kaiserinnen- und Prinzessinnenbildnisse, Frauenporträts, Mainz am Rhein, 1983

S. Hoog ed., Musée National Du Château De Versailles Catalogue: Les Sculptures I – Le Musée, Paris, 1993

R.W. Lightbown, “Isaac Besnier, Sculptor to Charles I and his work for Court Patrons, c. 1624 – 1634” in D. Howarth ed., Art and Patronage in Caroline Courts, Cambridge, 1993

P. Michel, Mazarin, prince des collectionneurs: Les collections et l'ameublement du Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661): Histoire et analyse, Paris, 1999

J. Raeder, Die antiken Skulpturen in Petworth House, Mainz am Rhein, 2000

J. Scott, The Pleasures of Antiquity: British Collections of Greece and Rome, New Haven and London, 2003

B. Borg, H. v. Hesberg, A. Linfert, Die antiken Skulpturen in Castle Howard, Wiesbaden, 2005

T. Longstaffe-Gowan, The gardens and parks at Hampton Court Palace, London, 2005

K. Knoll and C. Vorster (eds.), Katalog der Antiken Bildwerke III: Die Porträts, Munich, 2013, pp. 328-334, no. 74

C. Rowell ed., Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage, New Haven and London, 2013

P. Stewart, A Catalogue of the Sculpture Collection at Wilton House, Oxford, 2020

In terms of iconography, the present bust shows clear parallels with portraits of Lucilla’s mother Faustina the Younger. Not merely an expression of their biological kinship, these parallels were the result of a systematic approach to portraiture as a means of establishing the genealogical unity of the ruling family and the role of the emperor's wife in perpetuating the dynasty thanks to her fecunditas (“fertility”). The first scholar to propose a classification of the portraits of Faustina the Younger and Lucilla in the twentieth century was German archaeologist Max Wegner (1902-1998), whose typological approach was reprised and developed by Professor Klaus Fittschen (b. 1936) in a 1982 study dedicated solely to the likenesses of these two imperial women (see Related Literature). Analysing coins and statues, Fittschen identified nine types of Faustina’s portrait and posited that each was created to coincide with one of her pregnancies, a formula that he suggested was repeated for Lucilla and her three children, underscoring the centrality of fertility in relation to the image of Roman imperial women. Specifically, Fittschen described a “fifth type”, dateable to the birth of Faustina’s son Tiberius Aelius Antoninus in 152 A.D., as characterised by a rounded head and plump features, a slightly aquiline nose, large eyes, and uniformly wavy hair tied in a bun at the nape of the neck. As the German scholar explains, the fifth type of Faustina’s portrait formed the basis for one of the three types of portrait of Lucilla he codifies, exemplified by the present bust and known in four other variants: in Dresden (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Skulpturensammlung, inv. no. Hm 394, figs. 3a-d); in Rome (Musei Capitolini, inv. no. 1781, fig. 4); in Berlin (Staatliche Museen, Antikensammlung, inv. no. Sk 446, fig. 5); and in Tripoli (Archeological Museum, fig. 6). According to Fittschen, this type was likely devised in conjunction with Lucilla’s second pregnancy in 166 A.D., and the key to distinguishing between mother and daughter rests in the greater accentuation of the wave pattern found in Lucilla’s hair, as seen here and in the aforementioned variants (figs. 3-6). A deep wave pattern is also found in portraits of Faustina, but of the seventh type, where the hair is divided clearly into strands and braids, unlike in the present case.

One characteristic unique to the present likeness across the portraiture of Lucilla is the conformation of its bust, which includes the sitter’s right arm and hand emerging from her robes. Often found in full-length statues of Roman matrons, this arrangement is less frequent in busts and as such represents a key element towards tracing the history of our portrait. Inventorial records of ancient busts – especially female ones – in early-modern Europe are usually highly generic, with descriptions ranging from a simple name to even more broad definitions, such as “Head of a woman”. More specific evidence can, however, be provided by the existence of period copies, and in the case of the present bust five have been identified, dating to the seventeenth century.

The first one to consider is a bronze bust which has remained in the Royal Collection, since the reign of Charles I. The bust can be identified in the third group of drawings in the ‘Whitehall album’, which are thought to illustrate busts that were at Whitehall at the time of the Restoration.

The second is a plaster cast located over a doorframe on the Great Staircase of Ham House on the River Thames, which can be dated on the basis on documentary evidence to between about 1637 and 1672. Erected in 1610 by courtier Thomas Vavasour, in 1626 Ham House was leased and then bought by William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart – a close ally of King Charles I – who extended and embellished the existing building. After the family lost ownership of the house during the Civil War, the Earl’s eldest daughter Elizabeth acquired it back in 1650 and settled there with her first husband, Sir Lionel Tollemache. Following the latter’s death in 1669, Elizabeth married John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, in 1672, and together they set about enlarging and redecorating the house. Part of their renovations included work on the Great Staircase, executed in 1671-72 by one John Burnell, as recorded in a payment to him “Ffor severall Jobbs about ye house & cutting of holes in ye starecase for ye heads to stand in, & helping them up”. The heads mentioned in this entry correspond to the “4 heades of plaster” and “4 Marble Heads” listed in the same location in the 1677 inventory of Ham House, with the plaster ones – including the copy of the present Lucilla – visible in situ to this day. As Charles Avery argues in his analysis of the seventeenth century sculpture at Ham House, the plasters were probably executed by members of the Besniers émigré family of sculptors, who were active in London through most of the seventeenth century and arrived from France, perhaps as part of the retinue of Queen Henrietta Maria around 1625. During the Restoration, the Besniers were “involved specifically in the business of making casts in base materials, either directly after the Antique or from Le Sueur's earlier, royal copies”, which survived in their possession. However – Avery continues – “it is most likely that the plaster busts after the Antique were already in situ between the broken pediments of the Great Staircase as part of William Murray's classicising scheme of decoration, c. 1637-9. In that case, they could even have been cast by Isaac Besnier, who was available in London until 1643.”

Avery therefore dates the execution of the Ham House plaster copy of the present Lucilla to between c. 1637 and 1672, which is also the likely period of execution of another copy, in bronze, visible today on the entrance door of William III’s Little Banqueting House at Hampton Court. Not much is known about this version or how it became an integral part of the architecture at Hampton Court, but the Little Banqueting House was built in 1700, which offers a likely terminus ante quem for the casting of the bronze (assuming it is original to the building). The Besniers’ activity as court sculptors to Charles I and Charles II constitutes the most plausible explanation for this cast being part of a royal residence and also establishes a link with the plaster at Ham House, which is confirmed by the fact that these two copies appear to derive from the same mould, with very slight differences from the present marble noticeable in the folds of the drapery.

A third bust associated to the present portrait is at Wilton House in Wiltshire, home of the famous collection of sculpture assembled by Thomas Herbert, 8th Earl of Pembroke, in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Carved in marble, this bust was first recorded at Wilton in the manuscript catalogues of circa 1732 and Peter Stewart, who has compiled the recent catalogue raisonné of the sculpture at Wilton House, considers it a work of the first half of the seventeenth century, carved after the present prototype. Its facial features depart somewhat from those of our Lucilla, with more generic traits and blank pupils, but the structure of the bust, the appearance of the hair and the arrangement of the drapery are all closely comparable, confirming a direct link between the two busts. Further evidence of this connection is offered by comparison on the tabula of the socles of the two busts, each ornamented with frolicking putti, although they differ somewhat in representations of the puttis cavorting. This type of socle is ancient and can be found in a limited number of Roman portraits existing today, as will be discussed below. In terms of provenance, Stewart specifies that the Wilton bust – believed to be a portrait of Didia Clara by the 8th Earl, a name still associated with it – had probably been obtained from a Parisian source, possibly the collection of Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661), which Pembroke is documented to have acquired pieces from. Notably, Stewart adds that the present bust “may itself have been in the Mazarin collection”.

Among the most powerful politicians of the seventeenth century, Mazarin rose through the ranks of the French court to become chief minister to Louis XIII and Louis XIV, and in the process assembled one of the most illustrious collections of antiquities of the age, which was dispersed gradually by his descendants. Inventories of the Cardinal’s collection offer predominantly a general nomenclature of the statues, such as “Head of an Empress with Bust”, with several descriptions repeated more than once, making it difficult to securely trace the whereabouts of many of the items. The link with France proposed by Stewart, however, is undoubted, as the fourth copy of the present bust dateable to the seventeenth century – and the most accurate and highly finished one – is today in the Salon de l’Abondance at Versailles. Not part of the palace’s original decoration, this bronze is from the collection of the Louvre, and whilst no information has been published on its provenance, it is dated to the seventeenth century on stylistic grounds, and its facture and colour suggest it was cast in France. Now named “Poppaea Sabina”, possibly because it forms a pair with a bust of the eponymous Roman matron’s husband Nero, the Versailles bronze was previously titled “Faustina the Younger”.

It is worth pointing out here that a bust of Nero of the same type as the Versailles pair to the “Poppaea Sabina” – but in marble – can be found at Wilton House, which underlines that a connection most likely existed between the prototypes of these two portraits in the seventeenth century. This theory is reinforced by the fact that the Wilton Nero is set on a socle with frolicking putti, of the same shape and style as the ones that support the Wilton Didia Clara and the present Lucilla. Highly distinctive and rare, this type of socle has been recorded – with variations in the activities of the putti – in six additional busts: a Portrait of Trajan also at Wilton, but in very compromised condition; a Bust of Semiramis formerly at Wilton and only known through an engraving; an early Antonine period Portrait of a Young Man at Castle Howard; a mid-Antonine period Memorial Bust of a Girl at Petworth; a Portrait of Iulia Domna formerly in the collection of Frederick the Great of Prussia; and a headless Bust of a Youth in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Amongst these, the Portrait of a Young Man at Castle Howard and the Memorial Bust of a Girl at Petworth – which are catalogued as ancient by scholars and dated to the Antonine period – show a treatment of the back of the bust that is closely comparable to that in the present marble, further evidence of its dating to the 2nd century A.D. Presumably, the three busts were carved in the same workshop, which specialised in this type of ornamented socle. The Wilton Trajan is very weathered – Stewart believes its bust to be later than the head – while the Semiramis and the Iulia Domna are untraced, and the headless Youth in Istanbul has not been studied, but photographs of it and its provenance suggest it is indeed ancient. With regards to the seventeenth-century Nero and Didia Clara at Wilton, their socles are not integral to the busts and were likely adapted from earlier statues, perhaps damaged and discarded, or copied from ancient examples.

Having established that, at least by the seventeenth century, the present bust of Lucilla – otherwise identified as Faustina because of the aforementioned similarities between the portraits of these two empresses – was paired with an ancient and currently untraced portrait of Nero, and that the two were documented in France and England, more detailed hypotheses can be put forward regarding their provenance. Peter Stewart was the first to point out that the present bust may well have formed part of the collection of Cardinal Mazarin, a theory supported by the existence of the very fine, French seventeenth-century bronze copy of it in the Louvre. In the context of seventeenth-century collecting in France, a letter sent to Cardinal Mazarin in May 1653 by his agent in London, Monsieur de Bordeaux, stands out. The latter assured his patron that “many busts” could be found in the English capital – then in the chaotic aftermath of the Civil War, when aristocratic collections were being dispersed – and in a list of the ones he considered of the highest quality, de Bordeaux mentioned a Nero and a Faustina (without specifying whether it was the Elder or the Younger Faustina) in marble, “chez M. Guildorphe”, a francophone transliteration of the surname of George Geldorp (1580/95–1665), the painter and art dealer active in England between the reigns of Charles I and Charles II. Unfortunately, subsequent letters between Mazarin and his London agent do not explicitly name these busts again, and the Cardinal cryptically replied to de Bordeaux “As for statues and busts, I do not think we should consider it, since there aren't any so old that we couldn't find one of the same age when we wanted”. This, however, does not exclude the possibility that de Bordeaux ultimately found a French buyer for the busts, or that, even if he did not, he or Geldorp had casts taken of them, which then found their way to France and resulted in the bronzes now at Versailles. Where Geldorp might have sourced the busts of Nero and Faustina has not been possible to determine, but as the collections of antiquities assembled by Thomas, 14th Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), and George, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628) demonstrate, an appetite for ancient busts – which would flourish during the era of the Grand Tour – was already established in England in the first half of the seventeenth century. For example, busts of Nero and Faustina are recorded in the 1635 inventory of Buckingham’s suburban villa, Chelsea House, in the long gallery. Within a decade, as the political climate worsened for royalists, his son, the 2nd Duke, began selling off pieces from the collection, which was ultimately entirely dispersed. After the Restoration, English collectors and agents reinstated ties with Italian dealers and restorers in ancient marbles, especially based in Rome, where it is highly likely the present portrait had originally been discovered, and copied by a sculptor whose work – the so-called “Didia Clara” – subsequently made its way to Wilton House.

In the twentieth century, the present bust was owned by Arnold Machin (1911-1999), a sculptor and graphic designer famous for creating the profile portrait of Queen Elizabeth II for the decimal coinage introduced across the Commonwealth in 1968, and that for British postage stamps first issued in 1967.

Related Literature

J. Kennedy, A description of the antiquities and curiosities in Wilton-House. Illustrated with twenty-five engravings of some of the capital statues, bustos and relievos, London, 1769

M. Wegner, Das römische Herrscherbild: Die Herrscherbildnisse in antoninischer Zeit, vol. 4, section II, Berlin, 1939

K. Fittschen, Die Bildnistypen der Faustina Minor und die Fecunditas Augustae (Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Philologisch-historische Klasse, Dritte Folge CXXVI), Göttingen, 1982

K. Fittschen and P. Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts in den Capitolinischen Museen und den anderen Kommunalen Sammlungen der Stadt Rom III: Kaiserinnen- und Prinzessinnenbildnisse, Frauenporträts, Mainz am Rhein, 1983

S. Hoog ed., Musée National Du Château De Versailles Catalogue: Les Sculptures I – Le Musée, Paris, 1993

R.W. Lightbown, “Isaac Besnier, Sculptor to Charles I and his work for Court Patrons, c. 1624 – 1634” in D. Howarth ed., Art and Patronage in Caroline Courts, Cambridge, 1993

P. Michel, Mazarin, prince des collectionneurs: Les collections et l'ameublement du Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661): Histoire et analyse, Paris, 1999

J. Raeder, Die antiken Skulpturen in Petworth House, Mainz am Rhein, 2000

J. Scott, The Pleasures of Antiquity: British Collections of Greece and Rome, New Haven and London, 2003

B. Borg, H. v. Hesberg, A. Linfert, Die antiken Skulpturen in Castle Howard, Wiesbaden, 2005

T. Longstaffe-Gowan, The gardens and parks at Hampton Court Palace, London, 2005

K. Knoll and C. Vorster (eds.), Katalog der Antiken Bildwerke III: Die Porträts, Munich, 2013, pp. 328-334, no. 74

C. Rowell ed., Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage, New Haven and London, 2013

P. Stewart, A Catalogue of the Sculpture Collection at Wilton House, Oxford, 2020

Medium: Marble

Signature: 85 x 57 cm (33 ½ x 22 ⅜ in.) - 28 cm (11 in.) diameter, the socle

Provenance: Likely with George Geldorp (1580/95-1665), London, 1653

Probably in the collection of Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661), France

Arnold Machin, OBE RA FRSS (1911-1999), Garmelow Manor, Eccleshall, United Kingdom

Literature: P. Stewart, A Catalogue of the Sculpture Collection at Wilton House, Oxford, 2020, p. 162, under cat. no. 100

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie

-27. A Collection of Cameo and Intaglio Impressions_T639063181376242285.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)